David Schaumann, Head of English at John McGlashan College, shares his research into the use of key competencies as key motivators for changing the culture of students’ credit counting. He describes how approaching English in this way can open up new possibilities for more in-depth studies as students consider that learning is more than working towards credits.

Introduction

"Does this count for credits?"

Those of you who teach at the senior end of secondary schools, very likely just cringed. This ubiquitous question at the very centre of so many students’ 'must knows' is a frustration and a limitation that can be inherent within a National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) environment. It is understandable. Credits, merits, excellences, endorsements – all these things provide a tangible reward and therefore a clear sense of where students might best spend their time and energy. Unfortunately, if credits are the only motivator, when you take them away, or take away the need to accrue more, as “I’ve already passed level 3”, you take away the purpose of the learning. You take away the learning. There is an irony in the fact that NCEA itself is drawn from The New Zealand Curriculum yet this aspect of it seems to be at odds with the value of lifelong learning, espoused in the front part of this curriculum document. In fact, it seems to be diametrically opposed to being, "...actively involved lifelong learners". And if we dig further into the values and, especially the key competencies of our curriculum, we see a range of capacities developed with positioning our students to be able to tackle the dynamic challenges of 21st century life. These capacities are very often only given lip service, at best, as we concentrate on the ‘more important business’ of crunching those credits.

One of the things to consider within this context is that the issue of credit crunching isn’t something that comes from our students alone. Many of us who teach NCEA use the accruement of credits, and the achievement of a particular grade as both carrot and stick. In doing so, we find ourselves in the uncomfortable position of being complicit in a situation that we find frustrating and at odds with our values.

But, can we re-frame the values underpinning NCEA motivation, moving them away from the tangible and concrete, towards abstract perceptions of personal growth?

This was the fundamental question that I sought to answer during my action research as part of my Dr Vince Ham eFellowship in 2017, through CORE Education. My research was conducted with NCEA level 2 English students at John McGlashan College, an all-boys year 7–13 school in Dunedin. At John McGlashan we have quite a dip in achievement at level 2 – achievement is much stronger at levels 1 and 3. It was, therefore, a natural group to select to see if attainment could be raised. I do note the irony here – that one of the goals of moving focus away from attainment of credits, was the attainment of credits. However, as you will see, there is much more to it than this.

So, re-framing values was the goal. But where to start? The more refinement and reading that I did, the more that the power of the key competencies as a source of more meaningful, enabling motivation for my students came to the fore. And "power" is an interesting word in this context too. Guy Claxton’s Building Learning Power (2012) explores a range of "Palettes" of learning powers from which students can draw to grow their power to learn. He presents strong data to support the impact that these can have on student success. This and New Zealand’s own Bolstad, Hipkins, Boyd and McDowall’s Key Competencies for the Future (2014) were crucial in shaking up my own thinking about what really matters when it comes to the capacities our students develop; as was a presentation at our school by Richie Poulton of the Dunedin study, particularly his comment that life success is strongly influenced by what we consider soft skills, in particular, self-regulation and emotional intelligence.

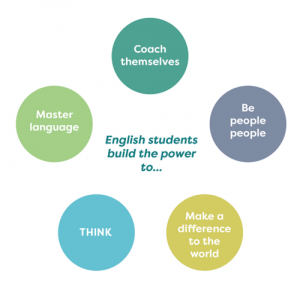

From these three sources, and after much discussion with others, I developed a range of "English Powers" (Figure 1) skills and capacities that we would focus on building through the everyday activities in our class. The hope was that the students would come to see these as the real "why" behind what we do in the class; that the idea of growth and development of powers that are very much in tune with life-long learning, would be what drives the desire to achieve, and that accruing credits would simply be a helpful by-product of this.

Methodology

After introducing this idea with my students, the next step was to work at framing what we were doing within this context. The "English Powers" became the learning intention behind each day’s work. Early in the process, I was asked:

"Can you “do” the key competencies to your students?"

This made me consider the importance of agency in ensuring students felt like we were in this together, rather than being subject to another whimsical change of practice after their teacher had been away at a course. My response was to approach the learning intention as a process of dialogue. I would introduce the activities and we would then discuss which of the English Powers this would be building. Then, crucially, we would co-construct success criteria. My students would lead this discussion, exploring what a powerful "Problem Solver" would look like, unpacking meaning from a text; or how they could become "World Changers" when considering how an oral presentation about an issue that they cared about, could reach an authentic audience and actually help facilitate a change of thinking.

I gathered qualitative data to see if changing the nature of the discussion about the point of it all, could actually change how my students thought and felt about what they were doing in my class; in fact, not just my class – the broader question was really, could it change the way they perceive all their learning?

The English Powers were embedded into each day’s learning. There was a great deal of discussion about building intellectual and emotional fitness and muscle. In fact this idea very strongly resonated with many of my students. We talked quite a lot about high performers – the All Blacks for example, and how their sole focus was not just playing the game, they need to be complete athletes, and so their growth involves a long list of traits: nutrition, psychology, muscle mass, endurance, strategy to name but a few. This discussion, and countless others, was designed to disrupt the credit crunching mindset.

Other ideas that married very well to the quest to see the truth in the value of the learning, are the growth mindset model (see Carol Dweck’s TED Talk) and James Nottingham’s "Learning Pit" – a diagrammatic representation of the learning process had a real resonance with my students, particularly when they were grappling with new and challenging unfamiliar texts. They could see how they were growing through this process, and could appreciate that it was not just their ability to unpack language features for example, they were also becoming intellectually fitter, they were becoming language masters, sophisticated thinkers, effective collaborators and so on.

All of this was complemented by considerable student agency. Where I could, I gave a choice of assessment mode, text, task, style – as much freedom as possible, in the belief that this freedom engages students more in their own learning and therefore is fertile ground for helping to engage them in a sense of its real worth. Much more so, than in other years, the conversations were about the "Why" behind the learning, and it was through this lens that students would make choices about the "What" they wanted to learn and "How" they could best present this learning.

Findings

Throughout the process, I frequently collected student voice and some more qualitative data, in the form of self-assessment rating scales. These and my observational journal were the main tools used to measure the impact of the change of practice. Some data on achievement was kept but, given the timeframe, the class size and the broad measure that NCEA uses – effectively four grade boundaries only – it was problematic to collect meaningful measure of this, with one notable exception that I will explain shortly.

Of all the English Powers we discussed, one came through as an outright winner in terms of what the students felt had helped change their understanding of their learning. The idea of being one's own coach – "Self-Coaching" we called it – a rewording of the key competency of managing self, strongly resonated with my students. In fact, this idea led to one of the best moments and strongest findings of the project. The conversation around it went a little like this:

“So we’re going to complete a second assessment for the Unfamiliar Text standard on Thursday. What do you think it is that we’re really assessing?”

“It’s really a test of how good we are at being a ‘Self-Coach’ isn’t it?”

Figure 2 – Data showing improvement from one unfamiliar text assessment to the next

First assessment is on the left, second, the right.

N – Not achieved; A - Achieved; M - Merit; E - Excellence

What followed, when I assessed this second attempt at this standard, was a spectacular leap in results; much higher than I’ve seen over this time frame before. It was a really powerful moment – my students could see that, by focusing on their power to coach themselves, they focused much more sharply on reflecting on their shortcomings the first time around, refining their techniques, and acting on feedback. Figure Two shows the degree to which student grades improved. It is probably no surprise then, that the rate of approval by the group, of the impact that this particular English Power averaged at 7.3/8 – 91%.

Of the other English Powers we explored, the ideas of becoming a "World Changer" and the "Language Master" (which, as I mentioned, was inextricably tied to the Learning Pit analogy) also scored highly – averaging at 6.5/8 – 81% in terms of the perception students had that they had made an impact upon them.

Disappointingly, the weakest of all the responses was one of the loftier goals: that students could see the use of the capacities they were growing in other curriculum areas, indeed in aspects of their lives. Upon reflection, it is likely over-reaching a little to hope that one intervention in one class could ripple out across the entire curriculum. The idea of a school wide approach to this is tantalisingly interesting though. A possible next step.

There were other findings though – more at the informal observation end of the spectrum, than those backed by quantitative data. Firstly, the impact on teacher student relationships in the class was very notable. Whilst I always enjoy good relationships, the positive tone and sense of all being in it together meant that this particular group had a real sense of team culture and was a great environment to be in – for both students and teacher. Moreover, the number of conversations about learning – preferences, gaps, strategies, risks – all of this was so much a part of the everyday classroom dialogue. I’m sure these two observations are symbiotic. Finally, there were some notable individual successes – students who achieved a result here or there far beyond anything that they had before.

Recommendations

All of this raises an interesting consideration. What if we don’t focus on building their capacity to excel in the key competencies instead of the academic achievement, or as well as their academic achievement but it is because we do this, that their academic achievement grows? Is there a point we can reach that sees our focus in the senior school on building the key competencies, the capacities that will lead to "lifelong learning", and raising achievement through this, rather than what seems to be the status quo – a passing consideration of these, then back to the "real work" crunching those credits. Given what’s really likely to lead to life success, perhaps we have got this the wrong way around. Perhaps it’s time for teachers to stop feeding the "credits at all costs" mentality and instead structure the purpose of their lessons around building capacity with the key competencies, so our students can grow towards becoming more confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners.

I would encourage you to strive to build a culture in your class where you really challenge the purpose of what you're doing. How often are we asked, "Where will I ever use this?", and how often is our response to this based around the worth of the credits that are attached to a given skill. But we don’t learn quadratic equations to become a mathematician, relativity to become a physicist, or read Shakespeare to become a playwright. The reality is that the brain power these exercises build, as well as our understandings of the world and the human condition, are the things that are absolutely transferable to all the challenges of the 21st century.

Consider what "powers" cognitive, emotional, social, cultural, communicative, or creative that are the real value that sits behind the work your students are doing, through which they might just happen to accrue credits for NCEA. And be confident that the real value of what you do is to foster the growth in capacities to think, relate to others, understand language symbols and texts, and participate and contribute to our world. And, this being the case, put it at the front of what you do – why you do what you do, rather than tack it to the side, and then get back to fostering the very thing that frustrates you: the mindset that it doesn’t matter if it’s not for credits. Perhaps it’s useful to picture it as in Figure 3.

Figure 3: NCEA vs focussing on the key competencies to foster lifelong learning

How it is now, how it might be.

Next steps

As a HOD, the next challenge is to try and broaden my findings beyond my own classroom, across the various levels of NCEA. And beyond the boundaries of this one curriculum area. I’m especially interested in the idea of "self-coaching" – I’m interested in how much this might function as the driver of all the others.

The question I’d really like to explore next is:

How can we build a culture where students "self-coach" to build their capacities across the other competencies?

I also wonder how much learner profiles could connect to this – I have a vision of students building a very clear understanding of how they are growing; what helps and hinders them in this process, and how we, their teachers, can best accelerate this. After all, we have known for a long time that the best teachers are very reflective, we cascade through spirals of inquiry in order to better our teaching. Perhaps we could help our students move through this same process, to become stronger learners, lifelong learners in fact, for whom credits are a useful byproduct, not the only point of anything they do.