Heemi McDonald is Deputy Principal of Rototuna Senior High School in Hamilton.

In this blog post Heemi shares his research into data collection through a Matauranga Māori lens using storytelling.

Ko te rito to pūrākau. Ko te pūrākau to reto.

Whatever is at the "centre" will be the "story" and understanding the story enables one to connect to that centre. The purpose for seeking to "know" a story influences how stories are received.

The stories that circulate in and around a school paint a picture of the school's culture and values, heroes and enemies, good points and bad, animating the actions and intentions of leaders, teachers, students, whānau, and community. By creating and sharing our stories, we define "who we are". Our identity is intricately woven into the tapestry of the narrative. Strong school leaders distinguish themselves by being good storytellers; voices that people listen to, are inspired by, and respect.

We need stories in order to understand ourselves and communicate who we are. We use stories to help us make sense of the world and the experiences of others. By sharing stories, we can better understand the conflicts of daily life and find explanations for how things fit together in the world.

Paul Auster, once said that telling stories is the only way we can create meaning in our lives and make sense of the world.

My learning journey

My own learning journey has provided ample fodder through which one might understand how story can influence perceptions about learning, identity creation, and identity affirmation.

Rarely is "data" viewed as a Māori construct or as Māori in any way. As a part of my research I considered how data practices might be informed by Mātauranga Māori or Māori ways of knowing. In order to realise the potential of "Māori achieving success as Māori", an exploration of areas, typically grounded in a Eurocentric narrative, required exploration. Central to this process was the desire to explore different types of data practices and how these data practices could be informed by Māori ways of knowing. By understanding the intersection between data practices and te Ao Māori, further insight might be gained into the experiences Māori students have with their learning data and how educators can enhance these experiences.

Furthermore, in seeking to understand how Mātauranga Māori might disrupt data practices, consideration was given to disruptive practices that might influence values positions in relation to learning data. In the exploration of data practices, three key concepts were considered: data about Māori; data for Māori; and data as Māori.

The Māori conceptual frameworks or Mātauranga Māori I explored included:

- Whakapapa – As a framework for exploring the ORIGINS of stories.

- Pakiwaitara – As STORIES themselves.

- Whakairo – As a framework through which to explore REPRESENTATIONS in stories.

- Raranga – As a framework through which CONNECTIONS are made within and beyond stories.

- Tukutuku – As a framework through which SIGNS/SYMBOLS are explored as markers or insights for future actions.

Pūrākau or "story" was used as a form of sense making including as a means of data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Research methods were underpinned by key Māori ethical frameworks. Included was a recognition of the centrality of whanaungatanga to the research process. Essential was the understanding that building and maintaining meaningful and reciprocal relationships influences the nature of the narrative generated by teachers and students.

Traditional Māori methods of storytelling focussed on accurately passing on knowledge, accuracy being paramount to the effective transmission of this knowledge. For Māori, an oral history means that getting the information "right" is essential for the dissemination and preservation of the story at the heart. If you don’t get it right, there is a distortion of what is or is not. The consequences of poor storytelling may have changed, but "getting it right" is still an essential element when telling Māori stories.

In a learning context, the following constructs were adapted to assist with understanding the nature of storytelling:

- Kōrero – the story itself

- Kaikōrero – (speaker as creator) the person telling the story (informal, incremental)

- Kaitaki kōrero – (narrator) the person or the "voice" whose viewpoint is used in telling a story

- Kiripuaki – (character) a person is viewed as a participant in a story over which they have no control or agency

- Kaituhi – (author) the person creating the story has the ability to characterise and construct unchecked

- Kaiwāwāhi – (editor) the ability for one to ‘edit’ a story and to adjust elements according to self determination

These concepts provided a lens through which stories could be connected to an indigenous way of knowing and articulated in a way that safeguards mana. These distinctions provide layers upon which an analysis of learning data could be undertaken. Firstly, seeking to understand the learning story itself, second, seeking to understand the story through the person creating it and the influence this has on the story, and finally, seeking to understand the way in which third party perspectives influence the conveyance beyond the immediate audience.

Driving questions

Guiding this research were two key questions:

- How can Māori ways of knowing disrupt current/established data practices?

- How can disruptive practices influence values positions about learning data?

For the participants, questions focused on understanding values positioning in relation to their understanding of learning data. Questions included but were not limited to:

- What does "valuable" mean to you?

- How valuable is your learning data to you?

- How valuable is the learning data to your practice?

- Why/how is your learning data important? (to you, your teacher, your whānau, your practice, your students)

Approach

The initial phase of the research involved uncovering perceptions about learning data and the value each of the participants placed on the data they identified. The focus of this phase was to better understand student and teacher perspectives about learning data. Sessions were conducted with both teachers and students, with each group being asked similar questions about learning data and the stories they believed existed in the data.

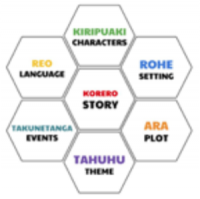

Participants were introduced to the concept of ‘story’ as a method for sharing or demonstrating understanding. Introduced was the idea that a story contains key components including characters, setting, language, events, plot and themes. In the case of teachers, they were asked to share a story, informed by data, about one of their students. For students, they were also asked to share a story, informed by data, about their own learning - sometimes this included exploring how others perceived them and their learning.

The hexagons pictured were used to assist with the korero development. Participants were not limited to the use of the hexagons, but they assisted with a wide exploration of the details surrounding their chosen student.

At this stage it must be noted, that care should be taken when discussing or sharing stories about students. They should be shared in a respectful way that protects the mana of all. Discussing students with anonymity is one way of protecting their mana and ensuring that narratives are focused on understanding perceptions as opposed to preconceptions about individuals.

While a story was being shared, observers drew, made notes, or summarised the story being told. They were encouraged not to interrupt the storytelling process, but to allow a full exploration of the story itself. Once the storyteller had finished, participants were encouraged to ‘retell’ the story in their own words, through pictures or any other means. This stage of the process helped to better understand perceptions held and to provide a reflective positioning through which the storyteller could understand how the information was received by others. It also served as a way through which participants could talk about the things they noticed in the data.

The key part of the retelling was to look for learning in the data. Multiple sessions were run to gather views and perceptions held before and after the introduction of Māori conceptual frameworks.

Early in the process, it became evident that incorporating a wide range of Māori concepts would be difficult due to the depth of understanding required by the participants. This lead to a focus on the concept of whakapapa and how this might be used to further unpack the stories told.

In both contextual and fixed views of Māori identity, whakapapa is generally agreed to be the key characteristic. For this research whakapapa was then introduced and explored as a way to more fully understand data stories. Whakapapa was viewed as knowing about the ‘descent’ (of data) and having a meaningful relationship to it. Essentially, whakapapa places learning data in a wider context and attempts to link the data to other aspects, groups, people, activities, etc. Through the use of this framework, participants were required to incorporate extensive background knowledge, explore linear and lateral pathways, organise learning experiences, connect learning experiences to development and creation, acknowledge individual tapu and representations. Ultimately, whakapapa served as a vehicle to identify the obligations of ALL parties in a learning story.

Once the initial retelling stage had been completed, participants were encouraged to apply a whakapapa lens to their conversations. Asking questions which prompted inquiry into the descent of data and how they influenced or were influential in the story. Some questions that were asked included:

- Why might that have happened?

- What things might have contributed to this situation?

- Who else might have influenced the situation?

- What might be missing from the story?

- Why is this the case?

My findings

Through the introduction and application of Māori centric data practices, data experiences were enhanced and supported the development of rangatiratanga and identity. In many instances, students suffer from the ‘one-way street of sense making’, subjected to stories told about them without any real agency to adjust or tell their own stories. Likewise, teachers view themselves as tellers of the story, seldom recognising how their implicit or explicit actions have influenced the development of a learning story.

This one-way traffic is a problem for every student but in particular Māori students. Simply incorporating Mātauranga Māori into practice will not completely stem the flow of traffic but may act as an impetus for greater change. In many cases Māori students already perceive education very differently to how it is intended to be received. Story may act as a language through which learning data can be explored and Mātauranga Māori can serve as the connection to one's identity.

When exploring this methodology, be ready! During the research process a student identified the difference between their ‘in’ and ‘out’ of school self. This revelation was both enlightening and startling. For many, school is viewed as a safe place and the beyond as uncertain and difficult. How often are these stories reflected in our actions as educators?

Every day teachers enter into the realm of story and have the ability to empower students to become editors of their own stories. At the heart of every story lives "rangatiratanga", a person's right to participate in making decisions about their learning journey and to have meaningful ways to decide how education might be provided for their benefit.

Data practices in schools

As educators, we collect copious amounts of data. In many schools, data practices are seen as eurocentric and are rarely viewed from any other perspective. Data flows from every aspect of a child's learning experience and plays an important role in the development of their learning story. However, data practices in many schools result in depersonalisation of information and these practices, once embedded, remain stagnant. In many instances, the challenge is centred on the notion that data, especially without meaningful patterns, is cold and with a lack of intrinsic meaning.

The problem is not with the data. The problem is with the stories. The ones we tell ourselves and our students and the stories our students figure on their own.

As a concept, storytelling permeates all cultures and is hardwired into us. We can't help but make sense of the world through story. Schools have yet to realise how their future might be shaped by story and there is still a lack of critical insight as to how and why storytelling can make a difference. For most schools, storytelling remains an abstract concept, at best reserved for English teachers and Senior Leaders when working a crowd, at worst, wishy-washy claptrap with no real value.

Making storytelling more tangible is a step toward helping students, teachers, and whānau further engage in education. If stories are so fundamental to the human experience, we need to figure out how to better incorporate them into the educational landscape. The question I am left asking is how might schools turn abstract notions of storytelling into practical tools for the benefit of all? Perhaps the answer lies in the fabric of the story of each school, student, teacher, and whānau. Perhaps story is the language through which learning may be explored and changed.

Further reading ...

The school that story built

Heemi McDonald was a 2017 CORE Education eFellow. His research was around 'story' and how students can use free flowing narrative to describe their learning. Heemi introduced students to the elements of karakia, waiata and whakapapa, having them retell their stories through the lens of māutauranga Māori. Heemi concluded that the data gathered from this process is different to traditional data about learning.

eFellow research – using narrative to encourage students to talk about their learning

eFellow Heemi McDonald discusses using narrative as a way of encouraging students to talk about their learning. Heemi describes surveying students using a free flowing narrative to enable students to share their stories, and talk about the value they placed on different aspects of their learning.