From New Zealand Curriculum to school curriculum

Curriculum design and review is a continuous, cyclic process.

The process involves making decisions about how to bring the national curriculum to life in a manner that addresses the particular needs, interests, and circumstances of the school and community. The design and review process requires a clear understanding of the intentions of The New Zealand Curriculum and of the values and expectations of the community.

Above all, it clarifies priorities for student learning, the ways in which those priorities will be addressed, and how student progress and the quality of teaching and learning will be assessed.

Curriculum change should build on existing good practice and aim to maximise the use of local resources and opportunities.

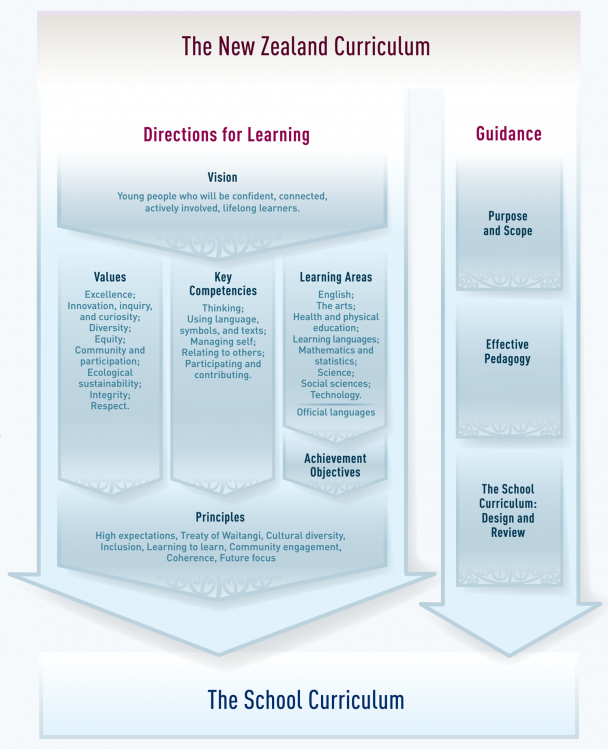

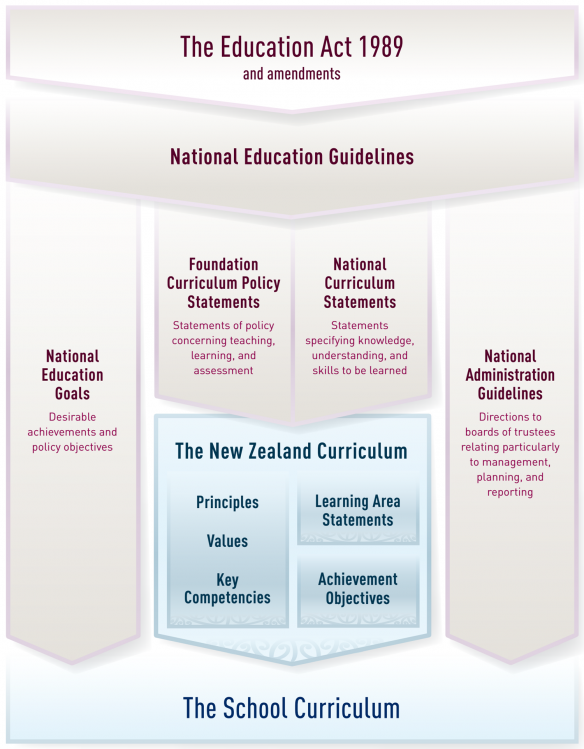

Curriculum is designed and interpreted in a three-stage process: as the national curriculum, the school curriculum, and the classroom curriculum.

The national curriculum provides the framework and common direction for schools, regardless of type, size, or location. It gives schools the scope, flexibility, and authority they need to design and shape their curriculum so that teaching and learning is meaningful and beneficial to their particular communities of students.

In turn, the design of each school’s curriculum should allow teachers the scope to make interpretations in response to the particular needs, interests, and talents of individuals and groups of students in their classes.

All New Zealand students should have the opportunity to receive a rich and balanced education that reflects the national curriculum.

The principles should underpin and guide the design, practice, and evaluation of curriculum at every stage.

The values, key competencies, and learning areas provide the basis for teaching and learning across schools and within schools. This learning will contribute to the realisation of a vision of young people who will be confident, connected, actively involved, lifelong learners.

Key considerations:

The relationship between The New Zealand Curriculum and the school curriculum

The New Zealand Curriculum sets the direction for teaching and learning in English-medium New Zealand schools. Note that it is a framework rather than a detailed plan.

This means that while every school curriculum must be clearly aligned with the intent of this document, schools have considerable flexibility when determining the detail. In doing this, they can draw on a wide range of ideas, resources, and models.

Schools are required to base their curriculum on the principles of The New Zealand Curriculum, to encourage and model the values, and to develop the key competencies at all year levels.

In years 1–10, schools are required to provide teaching and learning in English, the arts, health and physical education, mathematics and statistics, science, the social sciences, and technology.

Principles

The principles are the foundations of curriculum decision-making. They embody beliefs about the nature of the educational experience and the entitlement of students; they apply equally to all schools and to every aspect of the curriculum. Schools should be able to clearly demonstrate their commitment to the principles and to articulate how they are given affect in teaching and learning.

Values, key competencies, and learning areas

The New Zealand Curriculum identifies values to be encouraged and modelled and to be explored by students, key competencies that students will develop over time and in a range of settings, and learning areas that describe what they will come to know and do. Schools need to consider how each of these aspects of the curriculum will be promoted and developed in teaching and learning. They can do this in different ways.

Schools may, for example, decide to organise their curriculum around one of these three aspects (values, key competencies, or learning areas) and deliberately weave the other two through their programmes. Alternatively, they may decide to organise their curriculum around central themes, integrating values, key competencies, knowledge, and skills across a number of learning areas. Or they may use another approach or a combination of approaches.

The values, competencies, knowledge, and skills that students will need for addressing real-life situations are rarely confined to one part of the curriculum. Wherever possible, schools should aim to design their curriculum so that learning crosses apparent boundaries.

Values

Every school has a set of values. They are expressed in its philosophy, in the way it is organised, and in interpersonal relationships at every level. Following discussions with their communities, many schools list their values in their charters.

The New Zealand Curriculum identifies a number of values that have widespread community support. These values are to be encouraged and modelled, and they are to be explored by students. Schools need to consider how they can make the values an integral part of their curriculum and how they will monitor the effectiveness of the approach taken.

Key competencies

The key competencies are both end and means. They are a focus for learning – and they enable learning. They are the capabilities that young people need for growing, working, and participating in their communities and society.

The school curriculum should challenge students to use and develop the competencies across the range of learning areas and in increasingly complex and unfamiliar situations. Opportunities for doing this can often be integrated into existing programmes of work.

Use opportunities provided by the ways school environments and events are structured.

There will be times when students can initiate activities themselves. Such activities provide meaningful contexts for learning and self-assessment.

In practice, the key competencies are most often used in combination. When researching an issue of interest, for example, students are likely to need to:

- set and monitor personal goals, manage time frames, arrange activities, and reflect on and respond to ideas they encounter (managing self)

- interact, share ideas, and negotiate with a range of people (relating to others)

- call on a range of communities for information and use that information as a basis for action (participating and contributing)

- analyse and consider a variety of possible approaches to the issue at hand (thinking)

- create texts to record and communicate ideas, using language and symbols appropriate to the relevant learning area(s) (using language, symbols, and texts).

When designing and reviewing their curriculum, schools will need to consider how to encourage and monitor the development of the key competencies.

They will need to clarify their meaning for their students. They will also need to clarify the conditions that will help or hinder the development of the competencies, the extent to which they are being demonstrated, and how the school will evaluate the effectiveness of approaches intended to strengthen them.

With appropriate teacher guidance and feedback, all students should develop strategies for self-monitoring and collaborative evaluation of their performance in relation to suitable criteria. Self-assessments might involve students examining and discussing various kinds of evidence, making judgments about their progress, and setting further goals.

Learning areas

The learning area statements describe the essential nature of each learning area, how it can contribute to a young person’s education, and how it is structured. These statements, rather than the achievement objectives, should be the starting point for developing programmes of learning suited to students’ needs and interests. Schools are then able to select achievement objectives to fit those programmes.

None of the strands in the required learning areas is optional, but in some learning areas, particular strands may be emphasised at different times or in different years. Schools should have a clear rationale for doing this and should ensure that each strand receives due emphasis over the longer term.

Links between learning areas should be explored. This can lead, for example, to units of work or broad programmes designed to:

- develop students’ knowledge and understandings in relation to major social, political, and economic shifts of the day, for example, through studies of Asia and the Pacific Rim

- develop students’ financial capability, positioning them to make well-informed financial decisions throughout their lives.

Future focus

Future-focused issues are a rich source of learning opportunities. They encourage the making of connections across the learning areas, values, and key competencies, and they are relevant to students’ futures.

Such issues include:

-

sustainability – exploring the long-term impact of social, cultural, scientific, technological,

economic, or political practices on society and the environment

- citizenship – exploring what it means to be a citizen and to contribute to the development and well-being of society

- enterprise – exploring what it is to be innovative and entrepreneurial

- globalisation – exploring what it means to be part of a global community and to live amongst diverse cultures.

Achievement objectives

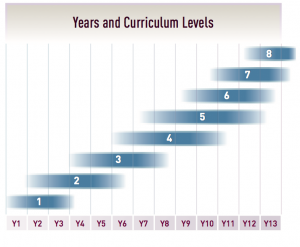

The achievement objectives found in The New Zealand Curriculum set out selected learning processes, knowledge, and skills relative to eight levels of learning. These desirable levels of knowledge, understanding, and skills represent progress towards broader outcomes that ultimately amount to deeper learning.

When designing and reviewing their curriculum, schools choose achievement objectives from each area to fit the learning needs of their students.

Some achievement objectives relate to skills or understandings that can be mastered within a particular learning level. Others are more complex and are developed with increasing sophistication across a number of learning levels. The broader and more complex an objective, the more significant it is likely to be for a student’s learning.

It is important for both planning and teaching purposes that schools provide clear statements of learning expectations that apply to particular levels or across a number of levels. These expectations should be stated in ways that help teachers, students, and parents to recognise, measure, discuss, and chart progress.

A school’s curriculum is likely to be well designed when:

- principals and teachers can show what it is that they want their students to learn and how their curriculum is designed to achieve this

- students are helped to build on existing learning and take it to higher levels. Students with special needs are given quality learning experiences that enable them to achieve, and students with special abilities and talents are given opportunities to work beyond formally described objectives

- the long view is taken: each student’s ultimate learning success is more important than the covering of particular achievement objectives.

Curriculum design and practice should begin with the premise that all students can learn and succeed (see the high expectations principle) and should recognise that, as all students are individuals, their learning may call for different approaches, different resourcing, and different goals (see the inclusion principle).

Assessment

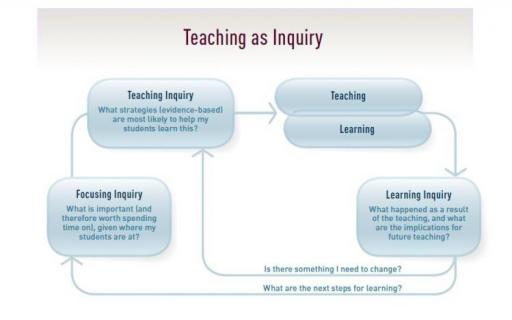

The primary purpose of assessment is to improve students’ learning and teachers’ teaching as both student and teacher respond to the information that it provides.

With this in mind, schools need to consider how they will gather, analyse, and use assessment information so that it is effective in meeting this purpose.

Assessment for the purpose of improving student learning is best understood as an ongoing process that arises out of the interaction between teaching and learning. It involves the focused and timely gathering, analysis, interpretation, and use of information that can provide evidence of student progress.

Much of this evidence is “of the moment”. Analysis and interpretation often take place in the mind of the teacher, who then uses the insights gained to shape their actions as they continue to work with their students.

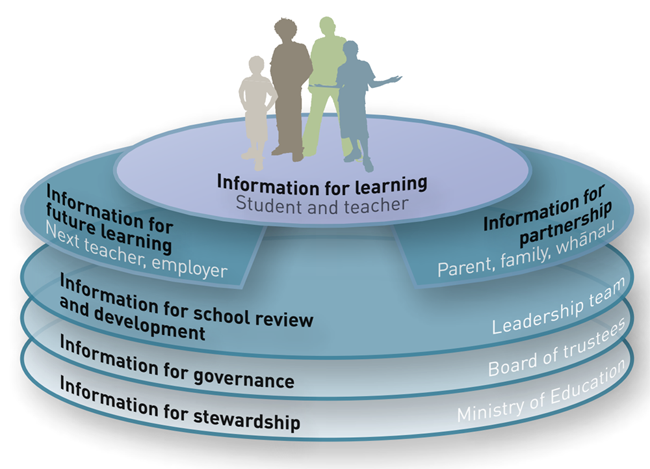

Use of assessment information

Select this link to open a text version of this diagram.

This diagram shows the different groups of people involved in supporting students’ learning and the purposes for which they need assessment information.

Some characteristics of effective assessment

Effective assessment:

- benefits students – It clarifies for them what they know and can do and what they still need to learn. When students see that they are making progress, their motivation is sustained and their confidence increases.

- involves students – They discuss, clarify, and reflect on their goals, strategies, and progress with their teachers, their parents, and one another. This develops students’ capacity for self- and peer assessment, which lead in turn to increased self-direction.

- supports teaching and learning goals – Students understand the desired outcomes and the criteria for success. Important outcomes are emphasised, and the teacher gives feedback that helps the students to reach them.

- is planned and communicated – Outcomes, teaching strategies, and assessment criteria are carefully matched. Students know in advance how and why they are to be assessed. The teacher’s programme planning is flexible so that they can make changes in response to new information, opportunities, or insights.

- is suited to the purpose – Evidence is obtained through a range of informal and formal assessment approaches. These approaches are chosen to suit the nature of the learning being assessed, the varied characteristics and experiences of the students, and the purpose for which the information is to be used.

- is valid and fair – Teachers obtain and interpret information from a range of sources and then base decisions on this evidence, using their professional judgment. Conclusions are most likely to be valid when the evidence for them comes from more than one assessment.

Assessment is integral to the teaching inquiry process because it is the basis for both the focusing inquiry and the learning inquiry.

School-wide assessment

Schools need to know what impact their programmes are having on student learning.

An important way of getting this information is by collecting and analysing school-wide assessment data. Schools can then use this information as the basis for changes to policies or programmes or changes to teaching practices as well as for reporting to the board of trustees, parents, and the Ministry of Education.

Assessment information may also be used to compare the relative achievement of different groups of students or to compare the achievement of the school’s students against national standards.

Assessment for national qualifications

The New Zealand Curriculum provides the basis for the ongoing development of achievement standards and unit standards registered on the National Qualifications Framework, which are designed to lead to the award of qualifications in years 11–13. These include the National Certificate of Educational Achievement and other national certificates that schools may choose to offer.

The New Zealand Curriculum, together with the Qualifications Framework, gives schools the flexibility to design and deliver programmes that will engage all students and offer them appropriate learning pathways. The flexibility of the qualifications system also allows schools to keep assessment to levels that are manageable and reasonable for both students and teachers. Not all aspects of the curriculum need to be formally assessed, and excessive high-stakes assessment in years 11–13 is to be avoided.

Learning pathways

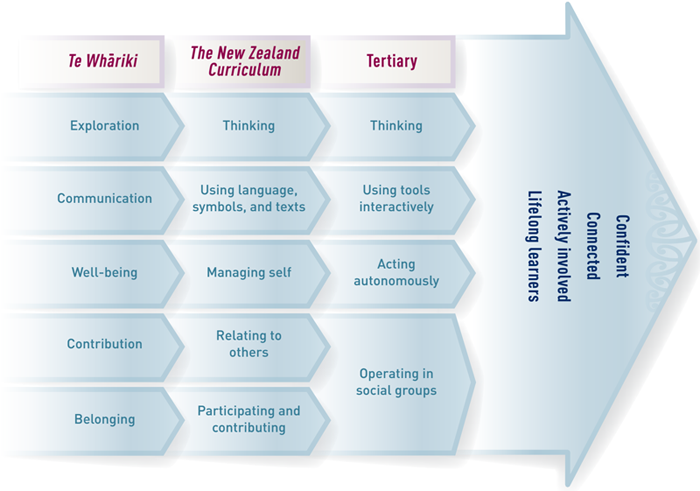

As students journey from early childhood through secondary school and, in many cases, on to tertiary training or tertiary education in one of its various forms, they should find that each stage of the journey prepares them for and connects well with the next. Schools can design their curriculum so that students find the transitions positive and have a clear sense of continuity and direction.

Early childhood learning

Te Whāriki: He Whāriki Mātauranga mō ngā Mokopuna o Aotearoa

This curriculum for early childhood education provides children with a foundation for ongoing learning. You can download a PDF of the document.

Four principles underpin the Te Whāriki: Empowerment, Holistic Development, Family and Community, and Relationships.

Te Whāriki includes five curriculum strands.

- Exploration – Mana Aotūroa

- Communication – Mana Reo

- Well-being – Mana Atu

- Contribution – Mana Tangata

- Belonging – Mana Whenua

Together, they provide a foundation for lifelong learning.

These strands correspond to the key competencies identified in this document.

Learning in years 1–6

The transition from early childhood education to school is supported when the school:

- fosters a child’s relationships with teachers and other children and affirms their identity

- builds on the learning experiences that the child brings with them

- considers the child’s whole experience of school

- is welcoming of family and whānau.

This new stage in children’s learning builds upon and makes connections with early childhood learning and experiences. Teaching and learning programmes are developed through a wide range of experiences across all learning areas, with a focus on literacy and numeracy along with the development of values and key competencies.

Learning in years 7–10

During these years, students have opportunities to achieve to the best of their abilities across the breadth and depth of the New Zealand Curriculum – values, key competencies, and learning areas – laying a foundation for living and for further learning.

A responsive curriculum will recognise that students in these years are undergoing rapid physical development, becoming increasingly socially aware, and encountering increasingly complex curriculum contexts. Particularly important are positive relationships with adults, opportunities for students to be involved in the community, and authentic learning experiences.

Students’ learning progress is closely linked to their ongoing development of literacy and numeracy skills. These continue to require focused teaching.

Learning in years 11–13

The New Zealand Curriculum allows for greater choice and specialisation as students approach the end of their school years and as their ideas about future direction become clearer. Schools recognise and provide for the diverse abilities and aspirations of their senior students in ways that enable them to appreciate and keep open a range of options for future study and work. Students can specialise within learning areas or take courses across or outside learning areas, depending on the choices that their schools are able to offer.

In these years, students gain credits towards a range of recognised qualifications. Schools can extend this range by making it possible for students to participate in programmes or studies offered by workplaces and tertiary institutions. Credits gained in this way can often be later transferred to tertiary qualifications.

The values and key competencies gain increasing significance for senior school students as they appreciate that these are the values and capabilities they will need as adults for successful living and working and for continued learning.

Tertiary education and employment

Tertiary education in its various forms offers students wide-ranging opportunities to pursue an area or areas of particular interest. Some tertiary education focuses on the highly specific skills and discipline knowledge required, for example, by trades, ICT, and health professions. In other cases, the emphasis is on more broadly applicable skills and theoretical understandings, developed and explored in depth, which provide a foundation for knowledge creation.

Tertiary education builds on the values, competencies, discipline knowledge, and qualifications that students have developed or gained during their school years. Recognising the importance of key competencies to success at tertiary level, the sector has identified four as crucial: thinking, using tools interactively, acting autonomously, and operating in social groups. These correspond closely to the five key competencies defined in this document.

In the past, many young people finished all formal learning when they left school. Today, all school leavers, including those who go directly into paid employment, should take every opportunity to continue learning and developing their capabilities. New Zealand needs its young people to be skilled and educated, able to contribute fully to its well-being, and able to meet the changing needs of the workplace and the economy.

The key competencies: Cross-sector alignment

This diagram suggests how the tertiary competencies align with those of Te Whāriki and The New Zealand Curriculum:

Select this link to open a text version of this diagram.