Simon is a second-year teacher at a small decile 5 kura kaupapa Māori. His iwi affiliations are Ngāti Kahungunu, Tūhoe, and Ngāpuhi. His students were in years 6, 7, and 8, and his inquiry focused on their learning in tikanga ā-iwi (social studies).

Professional learning is an important feature of the kura Simon teaches at. All the teachers participated in QTR&D. They collaborated to design and carry out their inquiry cycles and to make sense of their new learning. The tumuaki (school principal) participated in the first phase of the project, attended all presentations, and mentored the teachers. This collaboration was an important feature for all the kura who formed this QTR&D hub, with the majority of teachers in the three participating kura taking part.

Simon’s inquiry question was:

Will sharing learning intentions and co-constructing success criteria raise participation and achievement levels in tikanga ā-iwi in my class?

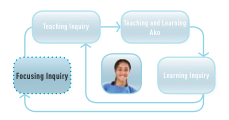

Simon’s focusing inquiry

What was important, given where Simon’s students were at?

Simon and his colleagues wanted to give greater emphasis to teaching and learning tikanga ā-iwi.

I’d like my class to look enthusiastically, positively, at the tikanga ā-iwi put before them. Our school, for much of the time, looks at the major curriculum areas, such as tuhituhi (writing), pānui (reading), and pāngarau (mathematics). I’d like us to give the other curriculum areas the same status throughout the school.

In preparation for the main part of his inquiry, Simon developed and taught a unit on the Kīngitanga. When Simon reflected on this unit, he realised that most of it had involved fact finding rather than exploring concepts that were deep and meaningful for his students. He decided that the purpose of his inquiry would be to improve his students' engagement and achievement in tikanga ā-iwi through fostering their ability to use the social inquiry process to reflect more deeply and critically about concepts and topics relevant to their lives. At the time of its involvement in QTR&D, this kura was relocating to a new site. This provided Simon with a context for his inquiry that was authentic and meaningful to his students.

Moving away from fact-finding projects in tikanga ā-iwi became a major focus for all teachers in the hub. As a first step, they co-constructed a planning template that could be used across kura and at different years. The intention was to ensure a clear focus on teaching and learning that would help students to develop knowledge and understanding about concepts and topics relevant to their lives. The template also reminded teachers of the need to plan for a social inquiry approach. Because they were teaching in a Māori-medium context, the teachers also needed to think through the language demands of the units they planned. They discussed a range of strategies for teaching and reinforcing vocabulary and included in the template a section for noting key vocabulary and sentence patterns that would be taught throughout their units.

What research evidence did Simon draw on?

One of the motivations for Simon’s inquiry was reading Teachers as Researchers: A Professional Necessity?, in which Viviane Robinson argues that teacher inquiry is central to sustainable school improvement, teacher development, and teacher professionalism.

'Good practice requires the ability [of teachers] to interrupt automatic classroom and institutional routines in order to inquire, in a sufficiently rigorous way, into the adequacy of their assumptions about the nature of students’ needs and how to meet them.' 2003, page 28

What evidence did Simon use from his own practice or that of his colleagues?

Using the template discussed above, the teachers conducted a first cycle of planning, teaching, and evaluating to gather baseline information in relation to their students’ knowledge, understanding, and skills in tikanga ā-iwi. This became the springboard for a second cycle of planning, teaching, and evaluating.

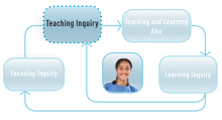

Simon’s teaching inquiry

What strategies were most likely to help Simon’s students learn what they needed to learn?

Simon reflected further on his professional reading and the findings from the Kīngitanga unit and decided that the primary focus for his own learning should be the effective use of learning intentions and success criteria. While he had always shared learning intentions with his students, he’d tended to speak about them quite briefly before moving on to the learning activities. He wondered whether part of the reason for his students’ lack of enthusiasm for tikanga ā-iwi was that they didn’t fully understand or recall the purpose of their learning.

Simon decided to keep the learning intentions on display as a reference point, constantly reminding the students of their learning objectives. This would also be a prompt for his own practice, reminding him to provide the students with the specific feedback they needed to improve their work as they went about it. He also decided that he would construct success criteria with the students, a practice that he had not carried out previously. He hoped that these changes would help the students to better understand the quality of the work he expected from them and to more effectively monitor their own learning.

Simon’s past practice had tended to be quite teacher-focused. He wanted to move towards more reciprocal relationships with his students that would build on their knowledge, skills, values, and identities as Māori:

To be Māori is unique and should be celebrated. Learning [happens best] in an environment where the teaching and learning is reciprocal and where power is shared – where my pedagogy, although evolving, sees my experiences being shared and where my students share their experiences; where commonality is our norm and being Māori is normal.

Simon’s selected focus for social inquiry was “adapting to change”. This focus was chosen because it coincided with the school shifting to the new kura and so presented an opportunity to look meaningfully at the concept of change as the students literally lived the experience. While much of their work was to be collaborative, poetry would provide opportunities for each student to express their personal thoughts and feelings.

Simon was keen to build the students’ ability to think and reason as they deepened their conceptual understandings about the key concepts. He adopted three strategies to achieve this:

- One strategy, with which the students were already familiar, was the use of De Bono’s “six thinking hats”.

- A second strategy, intended to connect with the students’ cultural heritage, was to share relevant whakataukī (proverbs) and to explore their deeper meanings by asking, “What makes this whakataukī important? What does it mean to me?”

- As a third strategy, Simon intended to allow time within the unit for students to collaboratively develop questions to focus their inquiry about change in the kura and at home.

What research evidence did Simon draw on?

Simon was influenced by Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (Aitken and Sinnema, 2008) and its evidence about the importance of making effective links to students’ lives. The synthesis identifies “Connection” as one of four mechanisms for enhancing learning in tikanga ā-iwi:

'This mechanism explains how students’ participation and understanding is enhanced when their teachers connect the content of learning to their lives. By making such connections, teachers increase the relevance of the learning for their students and encourage them to find parallels between new learning and their own experiences.' page 49

There is a considerable amount of literature about the importance of formative assessment or “assessment for learning”. Simon’s reading included research by Alton- Lee (2003), Clarke et al. (2003), Clarke (2001), and Hattie (1999). All these researchers are referred to in the various assessment resources provided on Te Kete Ipurangi’s page on formative assessment.

Simon read papers on the role of relationships in student learning. One was by Hawk et al. (2002), who examined the results of three research projects to identify the following characteristics of effective teacher relationships with Māori and Pasifika students: empathy, caring, mutual respect, “going the extra mile”, passion to enthuse and motivate, patience and perseverance, and belief in the students’ ability.

What evidence did Simon use from his own practice or that of his colleagues?

In Simon’s first year of teaching, he had worked to build productive relationships with his students. This provided a base on which to build:

As a new teacher last year, I struggled immensely to gain the trust of some of the students. But as the year went on and they got to know me, barriers started to dissolve. As I remained loyal to them and committed, the change in attitude of some of my students has been commendable. They are totally different this year. It is these very attitudes within the relationships that can enhance and lift Māori achievement.

Simon was fortunate in having access to models of the sorts of relationships he aspired to – for example, in the way the kura handled behavioural issues and in its management structure:

In the kura I teach at, there is a strong focus on being patient with the behaviour of some of the students. Often a one-on-one reciprocal approach is used to change behaviour and initiate learning, building on success, however small it may be, for that particular student …

The kura is governed by a Māori concept called “whānau whakahaere”, whereby all the parents and staff are responsible for the day-to-day running of the kura, from policy making to curriculum decision making. All whānau can be involved in the learning and teaching of their children.

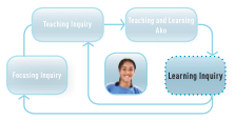

Simon’s learning inquiry

What happened as a result of Simon’s teaching, and what are the implications for his future teaching?

Simon observed and interviewed his students to find out whether the learning intentions and success criteria had helped. For the most part, he found that they had a greater understanding of what was required, and this had motivated them to work harder:

My students really think about meeting the success criteria satisfactorily. Having worked together to construct the criteria, they know what they wish to attain, and they know what I expect of them … The quality of their work has lifted, and the value they place on the work; they regularly refer to the success criteria to see if they are still on track.

Some of Simon’s younger students had still not fully grasped the concepts of learning intentions and success criteria by the end of the unit. Simon hopes that continuing to experience them in different contexts will help the students to deepen their understanding and use of them.

The inquiry reinforced for Simon the value of building a reciprocal learning relationship with students. However, it also reinforced the role of the teacher in providing guidance and the complexity of giving appropriate feedback and “feed forward”:

Giving feedback, you have to get it right for them. It’s hard working out what to say to each student. You have to find a way to make suggestions and point out comparisons … The important thing in a unit of this kind is that they can justify their decisions.

The selection of a learning context and key concepts that were relevant to the students’ lives had contributed to the students’ engagement in learning. They reflected deeply on what would be the same about the new kura, what would be different, and how they would adapt to the change. Through their discussions, they were able to have some input into decisions about the move, such as where their classroom should be and what colour it would be painted, where they should eat their lunch, and whether there should be separate playgrounds for the tuakana and teina students. One of the facilitators who supported Simon pointed out that:

Tikanga ā-iwi is about inquiry, but ideally, with social inquiry, it’s also social action. The content must be relevant and related to the students’ lives. The shift was a real event, and they had input into the decisions. The students had shown great creativity in developing success criteria related to the concepts of change and adaptation. As well as helping the students to understand the purpose of their learning, this process had engaged them in planning what they would do. For example, one of the criteria was that they would choose how to collaboratively present their learning. From over twenty initial suggestions, they agreed on two final methods: they took photos of the old kura to show what they were moving from, and they built three-dimensional models of what they thought the new kura should be like. They elaborated on this by pasting pictures and explanations of their decision-making process onto their models.

Poetry proved to be a successful means for students to capture their individual thoughts and feelings about the move. The class shared the new concepts and ideas they had explored, but each student was free to choose the form of poetry they would use to express themselves in te reo.

Simon reviewed the success of the three strategies he’d adopted:

- The “thinking hats” strategy had been useful for getting the students to think through the issues associated with their move while also making connections to their own lives and their personal values:

They’d put on the black hat: what’s negative about the new school? – “It’s stink having this new school. I’ll have to get up early and my mother will need to drive me.”

What happens when you put on the white hat? – “It’s cool that we’re allowed to skateboard after school. This is our school, we can do what we like.”

- Whakataukī capture beliefs and understandings that continue to be relevant to people today. By sharing and inquiring into whakataukī about change from their own iwi, the students were helped to cope with the change they were experiencing. One student shared this whakataukī, which suggests we must accept that sometimes we have to move on.

Ka mate kāinga tahi, ka ora kāinga rua. When one home dies, another takes its place.

- Simon had encouraged his students to develop questions to focus their inquiry. He found that while some students were able to frame such questions, others were reliant on him to support them to do so. He noted this as an area for development for some of his students.

Language was a key issue to emerge from the inquiries of Simon and other teachers in the hub. The teachers spent a great deal of time thinking about and discussing the vocabulary and particular language patterns associated with the areas they wished to explore with their classes. This included thinking about how they could describe key concepts and about the questions that would be most effective in helping to develop their students’ understandings. It also meant thinking about strategies they could use to effectively teach and reinforce the new vocabulary and language patterns of their units.

A specific issue was the language of formative assessment. Simon and his colleagues collaboratively developed standardised terms in te reo for expressions within formative assessment. Examples were whāinga ako (learning intention), paearu angitu (success criteria), and kōrero whakahoki (feedback). These terms were used across schools as part of the shared language developed by teachers involved within the QTR&D project.

Simon is keen to transfer what he has learned through this inquiry across the curriculum. He is now more careful to explain, display, and refer back to learning intentions in all areas and to co-construct success criteria with the students.

What research evidence did Simon draw on?

Simon also read Macfarlane (2004), who argues that we can create a sound foundation for Māori students’ learning by building on their cultural strengths and experiences. He presents the “Educultural Wheel”, which incorporates five interwoven concepts that cover all aspects of the classroom: whanaungatanga (building relationships), kotahitanga (ethic of bonding), manaakitanga (ethic of care), rangatiratanga (teacher effectiveness), and

pūmanawatanga (general classroom morale, pulse, or tone).

What evidence did Simon use from his own practice or that of his colleagues?

Simon’s interviews with the students provided valuable data on the effectiveness of his inquiry. When he asked a student whether he thought the learning intentions and success criteria had helped, the student replied, “Yes, because they inspire me to work.”

In previous units, one of Simon’s students had told Simon that he understood the learning intentions, but Simon felt that he in fact didn’t. After the unit, Simon observed that this boy more clearly understood what was to be learned and was more engaged in his work. He told Simon:

[I have to] be clear about what I’m doing when I’m working, as it is difficult if I don’t know. It is better if you write it up first on the whiteboard, because otherwise I forget your instructions about what I have to do.

Some of the students’ questions were quite challenging.

One student said:

I’ve been told that I have to go to another school. My choice was taken away from me. How come we weren’t asked if we want to go to a new school? The adults and the government made all these decisions, but they didn’t ask me!

Simon felt he had begun to establish a learning community in which the students thought about one another’s needs as well as their own:

In his group’s model, one boy included a box with a lift to meet the needs of a girl in a wheelchair, thinking of her needs in a two-storied building. It showed he was connecting with other peoples’ social needs, how other people would cope with the change.

What happened next?

Collaborative inquiry has had a significant effect on Simon’s practice. He continues to be explicit about learning intentions across the curriculum, and he makes it a regular practice to engage students in developing success criteria. This provides the basis for productive conversations with the students on their learning.

They can see where they’re going. Previously, I don’t think I took into consideration how young some of the students were, and I expected them to be reliant on their memory. Keeping the learning intentions and success criteria on display means that all the kids can start at the same point each day, and it makes it easier for me to prompt them: “How do you know if you’re successful?” “You made that up, I’ll help you get there.” We’re sharing the responsibility for learning. If they don’t succeed, they get a poor mark, and that reflects on my teaching and me.

Across the kura, Simon feels that better use is now made of the opportunities offered by tikanga ā-iwi.

We’re going to Rarotonga next term, so we’re planning our tikanga ā-iwi programme to pick up on that and build on it. We’ll focus on the similarities and differences between Māori and Cook Islands Māori. Is Cook Islands Māori culture iwi-based, hapū-based in the different ways villages are run? Do they have language-based schools there? We’re looking at the past and any connections between our genealogy and Rarotonga. The deeper ideas will be about valuing and maintaining connections with our origins, the kids looking at their origins in another context, and the maintenance of traditions.

Simon and his colleagues see no end to their professional learning. They continue to think about and apply their learning from this particular inquiry, and they are about to embark on a similar investigation, this time focused on learning and teaching in pūtaiao.

As a beginning teacher in a kura kaupapa Māori, with limited time in practice, I believe my pedagogy continues to evolve. Although pedagogy was discussed while I was training at university, I don’t believe I fully understood the implications it would have on me as a teacher. In my first year of teaching, I thought I was theoretically ready to teach. Armed with a university degree, I was going to change lives. The first life I changed was my own!

Reflective questions

What questions does this story raise for you and your colleagues about:

- the impact of different kinds of feedback on student learning and classroom relationships?

- the amount of responsibility students should be given in making decisions around their learning?

- the specific challenges of learning in te reo Māori?

- the degree to which learning opportunities at your school enable Māori students to live and learn confidently and proudly as Māori?

- the extent to which you use a shared language about and for learning?

- how student voice could be incorporated in decision making in your school community?

References

Aitken, G. and Sinnema, C. (2008). Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis. Report from the Medium Term Strategy Policy Division. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Clarke, S. (2001). Unlocking Formative Assessment: Practical Strategies for Enhancing Pupils’ Learning in the Primary Classroom. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Clarke, S., Timperley, H., and Hattie, J. (2003). Unlocking Formative Assessment: Practical Strategies for Enhancing Students’ Learning in the Primary and Intermediate Classroom. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett.

De Bono, E. (1985). Six Thinking Hats. Boston: Little Brown.

Hattie, J. (1999). Influences on Student Learning. Inaugural Professorial Lecture, University of Auckland, 2 August.

Hawk, K., Cowley, E., Hill, J., and Sutherland, S. (2002). The Importance of the Teacher/Student Relationship for Māori and Pasifika Students (PDF, 172KB). Set: Research Information for Teachers, no. 3, pp. 44–49.

Macfarlane, A. H. (2004). Kia hiwa ra! Listen to Culture — Māori Students’ Plea to Educators. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Robinson, V. (2003). Teachers as Researchers: A Professional Necessity? Set: Research Information for Teachers, no. 1, pp. 27–29.

Te Kete Ipurangi: Formative Assessment.

Published on: 26 Aug 2009

Return to top