Moana is an experienced teacher of year 5 and 6 students at a large decile 2 primary school where most of the students are Pasifika. She conducted her inquiry collaboratively with two of her colleagues. Each teacher followed the same process but focused on their own target group of students. The school had previously been engaged in extensive inquiry-based professional development focused on reading comprehension. This new investigation was focused on writing.

The inquiry question was:

Will incorporating explicit instructional strategies when teaching narrative writing have a positive impact on students’ writing?

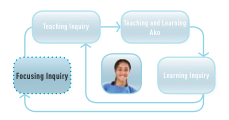

Moana’s focusing inquiry

What was important, given where Moana’s students were at?

Two factors were behind the decision that Moana and her colleagues made to embark upon this inquiry. First, results from asTTle (Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning) showed that most students’ writing achievement was below the national average. Second, their previous experience of professional development provided both a catalyst and a platform for further inquiry-based learning:

With what we knew now about reading, and the success already experienced in using an inquiry-based approach with reading comprehension – identifying a need, collecting evidence, making informed choices and decisions based on existing theories and research, implementing change, and analysing the effectiveness of change – we believed that the achievement levels in writing could be linked and also improved.

Having identified a general need, Moana and her colleagues went on to examine their student assessment data more closely to decide on the specific focus for their inquiry. Data from asTTle indicated that the students had difficulty in constructing a narrative and that they scored particularly poorly in content and structure. Each teacher selected four target students who had scored below expectation for many of the content areas measured by asTTle. Moana chose two boys and two girls who were Māori, Laos, Cook Islands Māori, and Samoan.

What research evidence did Moana draw on?

Moana was interested in the relationship between achievement patterns at her school and those across New Zealand. She sourced information about the national picture from In Focus: Achievement in Writing (Ministry of Education, 2006b), which includes the following:

'Pākehā/New Zealand European and Asian/Other students had higher average writing scores than Māori and Pasifika students. The difference, on average, was around 30 points, or one year. Nevertheless, on average, all ethnicities entered curriculum Level 3 in Year 8 and Level 4 in Year 10. The convergence in scores at Year 10 shows the gap between groups can be closed.' page 4

Moana and her colleagues referred back to the previous professional development in which they had participated. This had involved seven decile 1 schools within the Ministry of Education’s Mangere Analysis and Use of Student Achievement Data school improvement initiative. The teachers’ learning, and that of those who led the initiative, is described in the final report, Enhanced Teaching and Learning of Comprehension in Years 4–9 in Seven Mangere Schools (PDF, 2MB). The authors conclude that:

it is possible to develop more effective teaching that impacts directly on the reading comprehension achievement of Year 4–9 children. The level of gains overall were in the order of one year’s gain in addition to nationally expected progress over three years.

McNaughton et al., 2006, page xi

As well as examining the students’ asTTle data for narrative writing, Moana and her colleagues asked their target students what a narrative is. Moana’s target students responded as follows:

- Person who tells a story

- No idea

- Don’t know

- Character.

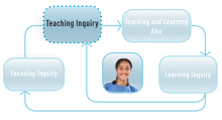

Moana's teaching inquiry

What strategies were most likely to help Moana’s students learn what they needed to learn?

Three considerations shaped Moana’s teaching inquiry:

- First, Moana and her colleagues realised that their current writing programmes were based around the processes of writing: forming intentions, crafting, reflecting, re-crafting, and presenting. They thought that their programmes might be more effective if they were to make deliberate connections between reading and writing.

- Second, the teachers thought that they needed to know more about instructional strategies (or “deliberate acts of teaching”) that are effective in improving literacy achievement for all students, and they needed to apply those strategies more deliberately in their own classrooms.

- Third, the teachers had to decide whether to focus on one genre or several. Their reading suggested that focusing on one genre would help the students make stronger links between reading and writing. The students’ asTTle results suggested that the genre should be narrative writing.

Moana and her colleagues drew these three threads together into their inquiry question. They also identified two sub-questions to help check their assumptions:

- Are we as teachers being explicit and deliberate enough to engage students as writers and improve their abilities?

- Are the students well equipped with the tools needed to write effectively?

The intervention took place in twenty-one guided-writing sessions over seven weeks. Each session incorporated specific instructional strategies for introducing students to new language tools and for helping them to explore the use of the toolsby other writers (including fellow students) and to apply them in their own writing. The planning was collaborative, and weekly meetings were built into the inquiry so that the teachers could reflect upon new evidence and make changes in response to their learning as they progressed.

The teachers hoped that the students would become more deliberate in their learning and that they would take greater ownership of it. For this reason, the teachers explained that they were conducting an inquiry into their teaching and that they would be learning alongside the students. They shared the asTTle data with the students, explaining what it meant and putting the results on the wall so that the students could monitor their own progress. At the start of each session, the teachers carefully explained the learning intentions, and they worked hard on ensuring that they were providing feedback that was specifically related to these intentions. The teachers were also very deliberate in explaining to the students that they could transfer their narrative writing skills to writing in other genres.

The teachers decided to use several other methods of data collection in addition to asTTle data. These were intended to give them deeper insight into their own practice and its impact on their students. They included:

- Student interviews: Videotaped interviews with the target students took place prior to and at the conclusion of the intervention. They were intended to provide information on what the students knew about narrative writing and how they perceived themselves as writers.

- Portfolio assessments: The teachers reviewed the students’ writing throughout the intervention. At its conclusion, the students were asked to provide written answers to questions about the deeper features of writing.

- Observations: Each teacher videotaped a 40-minute lesson early and late in the intervention in order to monitor their use of instructional strategies.

What research evidence did Moana draw on?

Moana and her colleagues explored a considerable amount of professional literature, but their key source was Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8 (Ministry of Education, 2006a). This handbook states that “Although students take many pathways in their literacy learning, teachers can apply the features of quality teaching practice effectively for all their students” (page 14). It explains that while conventional literacy practices have not always been effective for Māori and Pasifika students, those that it describes have been proven to help reduce disparities in student achievement.

Among those practices, Effective Literacy Practices in Years 5 to 8 describes seven instructional strategies that teachers commonly use: modelling, prompting, questioning, giving feedback, telling, explaining, and directing. It states that it is teachers’ judgment in the use of these

strategies that makes the difference for students:

Instructional strategies are the tools of effective practice. They are the deliberate acts of teaching that focus learning in order to meet a particular purpose. Instructional strategies are effective only when they impact positively on students’ learning.

page 78

Moana and her colleagues also reviewed what Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8 says about the reciprocal nature of reading and writing:

Studies of teachers who exemplify “best practice” have shown that these teachers continually make explicit the connections between reading and writing. Teachers who have a firm grasp of this reciprocal relationship recognise that writing is neither secondary to reading nor something to be taught separately from reading.

page 124

The teachers’ choice of a collaborative approach was informed, in part, by their reading of New Zealand research. Robinson (2003) says that effective professional development is “collegial, rather than individual, so that teams of teachers who share common tasks and responsibilities can learn together about how to do their jobs differently” (page 28).

What evidence did Moana use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

Moana and her colleagues conducted conversations in which they critiqued their current practice and identified areas for improvement:

'We questioned what we were doing and our practice at that time. A big concern was about learning intentions. The learning intentions weren’t shared for all the kids to see what we were doing; everything was a secret and a surprise …

Our practice tended to emphasise the experience of writing rather than gaining specific knowledge about language or exploring texts … We were teaching writing in terms of lists of features, like the key features of narrative writing or speeches, rather than the deeper features like audience or the language resources. We were expecting the kids to pick these up without really focusing on them. asTTle helped us to identify these important features. We wanted the kids to understand that there are different sorts of language they can use and that they can transfer these to their other writing. We wanted to help them to develop their own voice.'

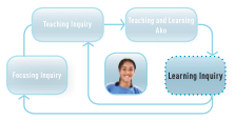

Moana’s learning inquiry

What happened as a result of Moana’s teaching, and what are the implications for her future teaching?

Moana and her colleagues used asTTle to check the impact of their intervention on their students. The average progress per year is generally 25–30 points for students at primary school. To everyone’s delight, the students improved at more than double this rate, with Moana’s target students improving by between 62 and 107 points in the course of the intervention. Because the students had also seen and understood the asTTle data, they were able to use the information to monitor their own progress:

'The kids got a lot of pleasure from the shifts, and they became more deliberate themselves. They were reflecting on what was important and talking about what did and didn’t work. They noticed when they didn’t shift: “ I know why I didn’t shift on my spelling – it’s because I didn’t do my spelling list!”

The teachers used their other data to get a better understanding of the changes for their students. The interview and portfolio-assessment responses showed, for example, that all the students now knew what a narrative was and could explain its features. They could talk about the types of language used in effective narrative writing, and their portfolios revealed greater creativity in their use of language.

Moana was a little disappointed that only two of the students said that their reading could give them ideas for writing narratives. The teachers and students had spent a great deal of time exploring examples of different aspects of writing, which the students then applied to their own writing in short snippets. On reflection, Moana thought that the students might have benefited from more opportunities to put their learning together in complete stories of their own.

The students’ responses revealed a more positive attitude towards writing and a greater sense of confidence in their own abilities. One concern that these responses raised for Moana resulted from the question “How good does the teacher think you are at writing?” Three of the initial responses were fairly positive, with one that was negative. After the intervention, the responses were all positive, but still not strongly so. Moana wondered if she should have provided more praise and acknowledgment of the students’ achievements. Her focus on writing and the use of more explicit instructional strategies may have caused her to “neglect the students’ identities as learners and the need to develop self-esteem and confidence in the writer”.

Evidence for this concern came from closer examination of Moana’s practice. Her first video observation showed that she provided no feedback at all. This meant that the students were not receiving explicit guidance on the next steps for their learning and were not being encouraged as much as Moana intended. At the next observation, four examples of feedback were observed. This was an improvement, but Moana felt that it was still not enough. An area for future inquiry will be how she can better manage time to provide more frequent and prompt feedback to her students.

Moana also commented on what she had learned about the deliberate use of instructional strategies. It was clear that they should be used in different combinations “to complement the learning intentions for each particular session”.

Questioning was the most common instructional tool used by Moana and her colleagues. They noted that, while many of the questions they posed were “carefully devised … in order to generate thoughtful discussions and to guide the students in understanding the concept being taught”, others were “quite random”.

When Moana viewed her first videotaped observation, she realised that she talked too much and needed to hand greater control over to the students. She did this in a number of ways, including asking questions that would generate discussion, allowing more time for that discussion, letting the students discover the language features within a text, and using the students’ own writing as a teaching resource:

'You’ve got to be able to step back and be less directive – give the students more autonomy. In some ways, I think it’s one of the harder things for experienced teachers to do!'

Sharing the asTTle data and talking about her own learning also helped:

'They knew it was part of our inquiry into our practice and we were learning along the way … The students could see I was creating a learning community.'

Moana felt that the support of her colleagues and senior management had been essential:

'Having the support of my colleagues made all the difference. We all had the same goals in mind, so we were able to look at our data, share our ideas, plan, do everything together. You become so enthused! The support from senior management was also important. They stood back, but they made it possible for us to do it.'

What research evidence did Moana draw on?

Moana and her colleagues’ conclusions about combining instructional strategies were reinforced by their reviewing of Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8:

Teachers use their professional judgment when deciding what particular combination of instructional strategies to use in a specific teaching situation. This will depend on the teacher’s instructional objective and the students’ learning goals, the students’ prior knowledge and experience, and the nature of the literacy session.

Ministry of Education, 2006a, page 91

The teachers’ discussion of their findings was also informed by Annan et al., who explore the nature of talk necessary for teachers’ professional discussions to be effective. They call this “learning talk”:

Learning talk is therefore talk about teaching which analyses, evaluates, and/or challenges the impact of teaching practices on student learning outcomes, and/or creates more effective practices to replace ineffective ones.

2003, pages 31–32

What evidence did Moana use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

The data the teachers collected provided evidence of improvement for both students and teachers. Table 1’s results are for a student who was in year 5 at the time of the intervention. Normal expectations for students in year 5 are that they will be at 2A/3B.

Prior to the intervention, the student was working below expectation for three of the four deeper features of writing: audience, content, and structure. Afterwards, this student was working at expectation for all four.

These are the students’ portfolio responses to a question about what a narrative is (see above for their pre-intervention responses):

- A story which is make believe like a fairytale and contains a setting, a character, a plot, and probably a

- A story that has a theme, plot, character, and an event

- A story with a plot, theme, event, characters

- A story which has four main parts, which are setting, characters, plot, and theme.

Table 2 is a tally of Moana’s use of specific instructional strategies early and late in the intervention. It shows the increase in feedback discussed above and, as a result of handing more control to the students, decreases in strategies such as explaining and directing.

Table 1: asTTLe narrative writing levels (B=below, | Student 1

| Deep features

| Surface features

|

|---|

|

| Audience

| Content

| Structure

| Language resources

| Grammar

| Punctuation

| Spelling

|

| Pre

| 2P

| 2P

| 2P

| 2A

| 3B

| 3P

| 3B

|

| Post

| 3P

| 3B

| 3B

| 3A

| 3A

| 4B

| 3A

|

| Shifts in sub-levels

| +3

| +2

| +2

| +3

| +2

| +2

| +2

|

Table 2: Observations of the teacher’s use of instructional strategies (deliberate acts of teaching) | Strategies/Deliberate acts

| Time 1 (number observed)

| Time 2 (number observed)

|

|---|

| Modelling

| 3

| 4

|

| Prompting

| 12

| 12

|

| Questioning

| 26

| 20

|

| Giving feedback

| 0

| 4

|

| Telling

| 4

| 3

|

| Explaining

| 12

| 8

|

| Directing

| 7

| 5

|

What happened next?

Following the inquiry, the class took part in a unit on poetry. Moana was pleased to find that the students were able to transfer the skills they had gained in narrative writing to their writing in another genre – in this case, poetry. “It stuck!” She found, too, that the students’ attitude to writing had changed, and they no longer saw it as a chore.

Moana finds she is now constantly asking herself questions about what she is doing in class and whether it is effective. She thinks this questioning is important: “How can you grow as a teacher if you don’t question your teaching?” While this is challenging, Moana feels that understanding the inquiry process means she is now better placed to answer such questions.

'It’s learning about myself. Before now, I felt I was plodding along. It all becomes more meaningful. You feel like you’ve fulfilled your purpose as a teacher! You’re not just going through the motions. It’s all about the kids now. That’s where the focus is.'

Since participating in the project, Moana has taken time out from teaching to complete her degree, which has involved more classroom-based inquiry. She is keen to get back to her school and continue her learning journey.

Reflective questions

What questions does this story raise for you and your colleagues about:

- the relationship between reading and writing?

- how to transfer knowledge about effective pedagogical practice into your own teaching?

- the concept of “effective pedagogy for all learners”?

- the value of collaborative inquiry?

- the value of sharing assessment data with students?

- the importance of feedback and “feed forward”?

- the deliberate use and combination of instructional strategies?

References

Annan, B., Lai, M. K., and Robinson, V. (2003). Teacher Talk to Improve Teaching Practices. Set: Research Information for

Teachers, no. 1, pp. 31–35.

McNaughton, S., MacDonald, S., Amituanai-Toloa, M., Lai, M., and Farry, S. (2006). Enhanced Teaching and Learning of Comprehension in Years 4–9 in Seven Mangere Schools: Final Report. Auckland: Woolf Fisher Research Centre, University of Auckland. Download file below

Enhanced Teaching and Learning of Comprehension in Years 4–9 in Seven Mangere Schools (PDF, 2MB)

Ministry of Education (2006a). Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2006b). In Focus: Achievement in Writing. In Student Achievement in New Zealand (information kit). Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (ongoing). asTTle: Assessment Tools for Teaching and Learning: He Pūnaha Aromatawai mō te Whakaako me te Ako. Auckland: University of Auckland School of Education.

Robinson, V. (2003). Teachers as Researchers: A Professional Necessity? Set: Research Information for Teachers, no. 1, pp.

27–29.

Published on: 26 Aug 2009

Return to top