Raewynne is an experienced teacher at a decile 3 school.

Her inquiry focused on two groups of year 5 and 6 students for whom she was providing literacy assistance away from their regular classrooms. Within this context, the focus was on social sciences and, in particular, the students’ understandings of the concepts of “cultural identity” and “cultural transmission”. The students were predominantly Māori and Pasifika, and Raewynne chose two students from each group as her target students.

Her inquiry question was:

How can I use Māori and Pasifika students’ past experiences, knowledge, and culture to enhance their achievement and learning?

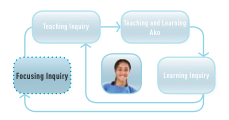

Raewynne’s focusing inquiry

What was important, given where Raewynne’s students were at?

At the start of the inquiry, Raewynne believed that she was catering well for her Māori and Pasifika students. She felt she had good relationships with them, was aware of their cultural differences, and made an effort to meet their needs. However, she was aware that they were not fully engaged in their learning:

'They often looked to me as their teacher for the answers or withdrew to a safe option and opted out.'

After reading a text by Russell Bishop (2001), Raewynne began to wonder whether there was something in the cultural context of her classroom that was preventing her Māori and Pasifika students from participating. She began by observing her students more closely and gathering information in relation to three sets of outcomes:

- the students’ understandings about cultural identity and cultural transmission;

- the students’ identities as learners;

- the students’ participation in and enthusiasm for classroom activities.

What research evidence did Raewynne draw on?

Raewynne read Russell Bishop’s “Changing Power Relations in Education: Kaupapa Māori Messages for Mainstream Institutions” (2001) and was inspired by the message that “culture counts”; that is, culture is not just an “add-on” but an intrinsic part of how each person sees and makes sense of the world.

A classroom in which culture counts is one where:

young people’s sense-making processes (cultures) are incorporated and enhanced, and where the existing knowledges of young people are seen as “acceptable” and “official”, so that their own stories provide the learning base to branch out into new fields of knowledge.

Bishop and Glynn, 2000, page 7

What evidence did Raewynne use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

Raewynne was able to document evidence in relation to the three sets of outcomes she’d selected: Understandings about cultural identity and cultural transmission: At the start of the intervention, her target students were unable to explain what culture was. Some seemed fearful of getting the wrong answer, and others were disengaged from the concept. Comments included:

- I don’t have any of that culture stuff.

- We don’t have a culture!

Identities as learners: Raewynne found that her target students didn’t value their own knowledge and experience, instead looking to the teacher as the authority. Comments included:

- Can you tell me what to do?

- I don’t know.

Participation in and enthusiasm for classroom activities: The students had little emotional connection with their learning, as demonstrated by both their body language and their reluctance to participate in discussions. When they did speak, their comments reflected this disengagement:

- Can you give me an idea, Miss? I don’t know what should happen.

- This is boring.

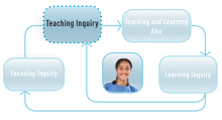

Raewynne’s teaching inquiry

What strategies were most likely to help Raewynne’s students learn what they needed to learn?

Raewynne realised that culture did not, in fact, “count” in her classroom in the way she had believed and that she needed to think about how she could become more culturally responsive.

'I wanted to avoid the traditional classroom where Bishop (2001) says “knowledge is determined by the teacher and children are required to leave their unique cultural identities at the door of the classroom or at the school gate” (p. 209) ... I came to realise that my background and cultural perspectives had been influencing the effectiveness of my teaching for Māori and Pasifika students. My journey of “learning, relearning, and unlearning” had begun (Wink, 2000).'

Raewynne’s attention was taken by one of the cases in Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration, which describes research with Samoan secondary students. This prompted her to develop a strategy of using family stories about valued cultural practices and experiences to help students connect the concepts of “cultural identity” and “cultural transmission” to their own lives. She wanted to communicate the idea that “culture” is not just about music, art, or drama but that, at a deeper level, it involves the small, everyday routines, practices, values, and beliefs that families pass down through the generations.

Raewynne modelled this idea by bringing some pieces of sewing to school and talking about the importance of craftwork in her family. She explained that her grandmother had taught her to sew, and now she was passing this skill on to her own children. Other staff members shared their stories, too. For example, one teacher showed the students her shell collection and talked about how her family had gathered it over the years.

The students recorded the idea and examples on diagrams and used Raewynne’s story as the basis for shared writing. They took this work home to share with their families and to show them the kinds of stories they were looking for. They then asked their parents and grandparents to suggest family stories that they could, in turn, share at school.

As they shared their family stories in class, the students recorded them on a chart and created a time line, showing the sequence in each story. Raewynne supported the students to discover links between their stories and those shared by the teachers. She hoped that this would allow the students to develop richer and more robust understandings of the key concepts underpinning the stories and that their cultural identities would be affirmed.

Raewynne understood that adopting this new strategy required a classroom environment where students felt safe to share their knowledge and experiences and to engage in rich discussions. Beginning the unit by telling her own story provided more than just a model of a family story; it was also intended as step towards creating a community of learners. Another of the cases in the social sciences best evidence synthesis describes a teacher’s use of the “What’s on Top?” strategy, a daily ritual in which the teacher and students sit in a circle and share events or issues from their out-of-school lives. Raewynne decided that she would try this in order to encourage greater participation in her class.

What research evidence did Raewynne draw on?

Raewynne read a draft version of Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (Aitken and Sinnema, 2008). This gave her access to a body of evidence about what works in social studies learning and why it works. The synthesis outlines four mechanisms that facilitate learning for diverse students in social sciences:

- Connection: Making connections to students’ lives;

- Alignment: Aligning experiences to student outcomes;

- Community: Building and sustaining a learning community;

- Interest: Designing experiences that interest students.

Two cases in the synthesis were important influences.

The first, based on a research report by McNeight (1998), describes how a teacher was able to improve learning outcomes for a group of Samoan students taking classical studies. The teacher:

- designed an approach in which the students undertook planned discussions about their classroom learning with a “significant other” at home, focusing on the connections they could make between ancient Rome and traditional Samoan culture;

- set up situations where the similarities and differences that had been discovered at home could be reflected upon at school, either one-on-one with the teacher or in small, teacher-directed focus groups.

The second influential case from the synthesis is based on a doctoral thesis by Sewell (2006). The case describes how the author worked with a teacher to create a classroom community of learners in which the students were enacting their learning about joint participation. The “What’s on Top?” strategy was important in creating a classroom environment in which the teacher and students could openly share what was in their hearts and minds.

What evidence did Raewynne use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

When Raewynne reflected honestly on her past practice, she found that it fell short of her personal ideals. Some of her discoveries included the following:

'I found the places or people to study. I didn’t consider the children’s past experiences and knowledge as real social studies. I thought social studies was out in the world and I had to bring it into the classroom.

As a teacher, I knew that a good relationship with my students was important within the classroom, but I didn’t think that my traditional, teacher- dominated pedagogy was detracting from students’ learning.

I didn’t consciously listen to student voice or utilise it in future teaching. I decided what was taught and how it was taught. I was directing the learning, and I thought I had to provide all of the direction for future learning and the motivation for its success. '

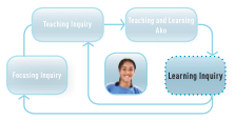

Raewynne’s learning inquiry

What happened as a result of Raewynne’s teaching, and what are the implications for her future teaching?

As the intervention proceeded, Raewynne continued to collect evidence about her own practice and its impact on her students’ learning. By the end of her inquiry, Raewynne was able to identify some significant shifts in her practice and benefits for both herself and her students from the experiences they had shared:

'Learning was based in the shared past experiences of the students and me. Through sharing and discussion, new learning was co-constructed, connections were made, and generalisations developed. Ideas and concepts related directly to our lives. We were the main resource for learning … The power of family stories as a resource for learning has been one of the most defining successes of this intervention. The use of their cultural background and experiences engaged the students in their learning, helped develop new understandings, and empowered them with new confidence and motivation … In one brainstorming session on family culture, we were filling in our own charts. I did one, too, and as we all worked together and took ideas from each other, the students were suddenly struck by how much they actually did know.'

Raewynne also reflected on what she had learned specifically about improving outcomes for Māori and Pasifika students:

'It’s more than just doing some Māori stuff in the classroom. It’s not just a mihi, and a greeting, and ticking that off. That’s important, but it shouldn’t be all that happens. It’s about incorporating students’ lives in the learning, valuing and caring for them as individuals, and valuing what they bring with them. I think it’s about knowing your students and who they are, not just as a Māori child but as a Māori child within a certain family. The next thing is providing a learning environment where that child from that family is comfortable. Not the family I as a teacher think they come from but finding out where they do come from. I think it’s a huge ask if you’re going to do that for every child in your class. But there’s lots of research that shows there are ways of providing an environment where those positive learning relationships can happen more easily. Then it’s about teacher expectations – expecting that they can learn and their knowing that you expect them to learn. With all of that, you can co-construct meaning through dialogue that develops and cements key concepts. It’s what Bishop says about sharing power – ako. We can share in creating knowledge through learning conversations rather than my having to be the fount of all knowledge.'

What research evidence did Raewynne draw on?

Raewynne found that the social sciences best evidence synthesis helped her to make sense of what had happened to her students as a consequence of the changes in her pedagogy. She used the four mechanisms as a framework for explaining what had happened in her classroom:

- Connection: The family stories were a means of embedding the learning in the students’ lives so that they could contribute from a position of strength. Raewynne found herself listening more often and more carefully to what the students said and then using her resulting understandings as a platform for further learning.

- Alignment: The repeated opportunities to share their own family stories and listen to those of others had enabled the students to fix their understandings about cultural transmission and cultural identity in their memories.

- Community: The students needed to feel safe to share their family stories; once they did, the process of telling and listening to one another’s stories contributed to building a community of learners where teacher and students could learn with and from each other.

- Interest: The use of their own and their families’stories as a resource for learning was deeply motivating for students.

(See Story 1 for another example of the use of the mechanisms.)

What evidence did Raewynne use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

Raewynne observed shifts in three sets of student outcomes:

Understandings about cultural identity and cultural transmission: The depth of this shift was revealed by the student who had earlier said, “I don’t have any of that culture stuff.” In a spontaneous comment made towards the end of the intervention, she said:

'Miss, you know that culture stuff we’re learning? Language is the same as culture ‘cause as a baby they listen to what they’re saying and they learn from it.'

Identities as learners: The students realised that they had knowledge, ideas, and experiences that were relevant and worth sharing. Family stories included:

'Sport: First, it started with my grandad. He played rugby. It has been passed down. I play sports because everyone in my family did from my dad’s side.'

'Gardening: My mum told me to say that my great grandparents used to grow stuff. Like, instead of getting their peaches from the supermarket, they used to cut them up and put them in this juice kind of thing … And it's been passed on from my great-grandma and great-grandad to my nana, and then to my mum. She just grows plants everywhere.'

'Art: From my great great grandfather … he did drawings … and my dad does paintings and drawings … My brother started doing art up in Auckland. When he was in primary school in Auckland, he became the school’s artist.'

Participation in and enthusiasm for classroom activities: The students participated eagerly in discussions of their family stories. Raewynne observed, for example, that they were:

- motivated enough to talk to parents at home about their work;

- prepared with family stories when it was time to share with the group;

- able to recall, discuss, and compare others’ family stories in later discussions.

What happened next?

Comments from the students’ regular teachers indicate that the students are participating much more confidently.

This seems to reflect a significant change in attitude. The students now see themselves as learners and are willing to contribute and “have a go”. The changes in pedagogy have also had a positive effect on the students’ achievement in literacy – for example, the students are better able to create and make meaning through discussion. Raewynne has made permanent changes in her practice. She is allowing more time for getting to know her students well and for creating a community of learners. She is giving herself permission to engage in extended dialogue with her students, without worrying that she should be getting on to the next item in her lesson plan. Learning is based around key concepts, and this has led to greater focus for both Raewynne and her students. Learning experiences build on the knowledge, life experiences, and interests of the students.

Raewynne is continually renewing her inquiry cycle with each new group of students:

You see it making a difference – how can you not keep doing it? The results speak for themselves!

Reflective questions

What questions does this story raise for you and your colleagues about:

- the degree to which your students’ cultural background, knowledge, and experiences count in teaching and learning at your school?

- the use of storytelling to affirm cultural identity and transmit knowledge?

- the partnerships you have with your students’ homes and communities and the contribution of these partnerships to student learning?

- the relationships you have with your students and whether those relationships enable mutual learning?

- the degree to which you share power and decision making in your class?

References

Aitken, G. and Sinnema, C. (2008). Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education

Bishop, R. (2001). Changing Power Relations in Education: Kaupapa Māori Messages for Mainstream Institutions. In The Professional Practice of Teaching, 2nd ed., ed. C. McGee and D. Fraser. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R. and Glynn, T. (2000). Kaupapa Māori Messages for the Mainstream. Set: Research Information for Teachers, no. 1, pp. 4–7.

Wink, J. (2000). Critical Pedagogy: Notes from the Real World. 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Published on: 26 Aug 2009

Return to top