Overview | The focusing inquiry | The teaching inquiry | The learning inquiry | References

If you cannot view or read this diagram select this link to open a text version >>

Overview

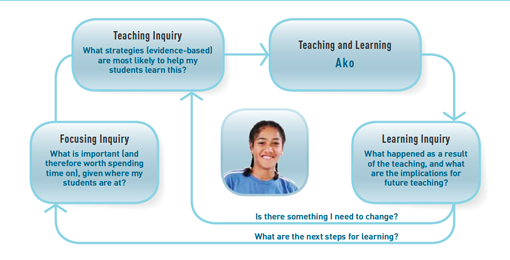

The New Zealand Curriculum (pages 34–35) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (pages 13–16) describe some of the teaching approaches that research shows to have a consistently positive impact on student learning. However, they stress that there is no formula that will work for every student in every situation.

Since any teaching strategy works differently in different contexts for different students, effective pedagogy requires that teachers inquire into the impact of their teaching on their students.

Ministry of Education, 2007b, page 35

The fundamental purpose of the Teaching as Inquiry cycle is to achieve improved outcomes for all students. Less obviously, but very importantly, the cycle is an organising framework that teachers can use to help them learn from their practice and build greater knowledge.

In the focusing inquiry, teachers identify the outcomes they want their students to achieve. They consider how their students are doing in relation to those outcomes, and they ask what their students need to learn next in order to achieve them.

In the teaching inquiry, teachers select teaching strategies that will support their students to achieve these outcomes. This involves asking questions about how well current strategies are working and whether others might be more successful. Teachers search their own and their colleagues’ past practice for strategies that may be more effective, and they also look in the research literature to see what has worked in other contexts. They seek evidence that their selected strategies really have worked for other students, and they set up processes for capturing evidence about whether the strategies are working for their own students.

The learning inquiry takes place both during and after teaching as teachers monitor their students’ progress towards the identified outcomes and reflect on what this tells them. Teachers use this new information to decide what to do next to ensure continued improvement in student achievement and in their own practice.

Although teachers can work in this way independently, it is more effective when they support one another in their inquiries. We all have basic beliefs and assumptions that guide our thinking and behaviour but of which we may be unaware. We need other people to provide us with different perspectives and to share their ideas, knowledge, and experiences.

What does the literature say?

Australian educator Alan Reid tells us that all educators need to be:

"professionals who are able to theorise systematically and rigorously in different learning contexts about their professional practices – including the issues, problems, concerns, dilemmas, contradictions and interesting situations that confront them in their daily professional lives; and can develop, implement and evaluate strategies to address these. That is, educators are understood as people who learn from teaching rather than as people who have finished learning how to teach." (2004, page 2)

The New Zealand Curriculum describes the Teaching as Inquiry cycle and the idea of purposeful assessment (page 39). Assessment is one of the tools that inquiring teachers use to improve their students’ learning and their own teaching. You can find resources to spark discussion about these and other related ideas on The New Zealand Curriculum Online.

Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES] (2008)

A publication that is part of a series in the Ministry of Education programme.

The the aim of each publication is to identify, evaluate, analyse, and make accessible evidence that links teaching approaches to enhanced outcomes for diverse learners.

The cycle is discussed in section 2.2 of the synthesis.

Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES] (2003)

Emphasises the importance of focusing on student outcomes and using both research evidence and assessment information to improve teaching and learning.

The publication stresses the importance of making links between the cultural contexts children experience at home and those they experience at school. It also highlights the need to ensure that teaching is responsive to students’ learning processes.

Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES] (2007)

Confirms what many teachers had always suspected – that teacher learning is of crucial importance to student learning.

The work describes the kinds of professional learning opportunities for teachers that make a real difference to student outcomes.

Example from Quality Teaching Research and Development (QTR&D)

Reflecting back on her inquiry, one of the teachers commented on the depth of learning she had experienced through questioning her everyday classroom practices:

"Through this journey, I have discovered that my classroom was not culturally inclusive for all my students.

Many of my Māori and Pasifika students were disadvantaged by the way I taught. This was a hard lesson to learn and accept.

This journey has changed my thinking about teaching and learning. Most importantly, I have had to question why and how I do things in my classroom.

My teaching is now based on a better understanding of social studies and has become more conceptually focused. In order to utilise family stories effectively as a resource, I have begun to develop a community of learners where reciprocal teaching, strong student–teacher relationships, and quality dialogue have become important parts of the learning environment."

Return to top

The focusing inquiry

This focusing inquiry establishes a baseline and a direction. The teacher uses all available information to determine what their students have already learned and what they need to learn next.

Ministry of Education, 2007b, page 35

The key question for the focusing inquiry is: What is important (and therefore worth spending time on), given where my students are at?

The teachers in QTR&D began their inquiries with a sense of personal responsibility for the achievement of their Māori and Pasifika students. They also believed that learning more about culturally responsive pedagogies and engaging in inquiry would help them in their commitment to improve those students’ outcomes.

During their focusing inquiries, they each began to draft an inquiry question that related to a particular issue of concern or interest in their class. They also selected a group of students to focus on and a set of outcomes that they wanted them to achieve. Focusing on a small group made it much easier for the teachers to evaluate the impact of the changes they made to their practice.

The teachers gathered data to find out how their students were doing in relation to the outcomes they had prioritised. They sought this data from a wide variety of sources, including student achievement records, observations, audio and video recordings, interviews, questionnaires, and standardised assessment tools.

For many, this initial set of data became “baseline data” that they could compare to later data to identify shifts and plan next steps. When the teachers analysed their baseline data, their focus was not just on their students but also on how they themselves had contributed to the current patterns of student achievement and what it was they might need to learn in order to help their students do better.

What does the literature say?

Helen Timperley has derived ten key principles from the best evidence synthesis of research on teacher professional learning and development. One of those principles is that “Information about what students need to know and do is used to identify what teachers need to know and do” (2008, page 13).

A number of New Zealand educational texts stress the critical role of teachers and school leaders in using inquiry to solve instructional problems and improve student achievement. Two examples that serve as practical guides on inquiry-based practice are Using Evidence in Teaching Practice (Timperley and Parr, 2004) and Practitioner Research for Educators (Robinson and Lai, 2006). The latter argue that:

"Good teaching and good decisions are based on high-quality information, not on taken-for-granted assumptions about the causes of children’s reading failure or the worth of new curriculum resources. The quality of information improves when everyone is open to the possibility that what they had previously taken for granted may not stand up to scrutiny. Teachers who are skilled in processes of inquiry can detect weaknesses in their own thinking about practice and help others to do the same." (page 6)

Examples from QTR&D

The teachers began their inquiries from many different starting points. One teacher began by carefully observing his students and reflecting on what he saw.

"In my year nine mathematics class, it is difficult to engage every child in the group to discuss their mathematical strategies. Some students are reluctant to contribute to discussions, due to more dominant personalities monopolising discussions. Other students often avoid paying attention to tasks, and the subject matter can tend to take different directions. Opportunities to share mathematical ideas are limited due to the barriers stated above. Therefore, the major question arising from these experiences is: 'How can I provide equal opportunities to engage students in sharing their mathematical strategies in group situations?'"

Another teacher began by assessing her target students and using this information to identify their learning needs:

"The students selected for the project scored poorly in the STAR subtest 2, and had achieved stanine 1 in the STAR test at the beginning of the year (February 2007). That is, they came in the lowest 4% of all pupils in the same age group nationwide. They generally have difficulties in word recognition, sentence and paragraph comprehension, word meanings, language of advertising, and understanding styles of writing."

Understanding expectations for achievement

For teachers to understand how their students are doing and what their next learning steps should be, they need to know about the expected rate of progress for students at different levels of the curriculum. The Ministry of Education provides many websites and other resources to help teachers and school leaders understand these expectations. It also provides resources to help teachers and school leaders gather and analyse data about their students and use that information to plan for their own and their students’ learning. These resources include The New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, the various teacher handbooks, and the many different assessment tools. Te Kete Ipurangi sites on Assessment and Aromatawai provide good starting points for finding this information. The New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa set the broad direction and outcomes.

The New Zealand Curriculum and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa set the broad direction and outcomes for students’ learning. The National Standards provide reference points at specified stages in students’ schooling to help students, teachers, and parents understand what students should achieve and by when. It should be remembered, however, that students start at different points and progress at different rates, so when achievement is being interpreted, rate of progress needs to be considered as well as achievement against a particular standard.

Return to top

The teaching inquiry

In this teaching inquiry, the teacher uses evidence from research and from their own past practice and that of colleagues to plan teaching and learning opportunities aimed at achieving the outcomes prioritised in the focusing inquiry.

Ministry of Education, 2007b, page 35

The key question for the teaching inquiry is: What strategies (evidence-based) are most likely to help my students learn what they need to learn?

The teachers in QTR&D wanted to improve their teaching by becoming more culturally responsive to their Māori and Pasifika students. In each hub, the teachers began by reading, thinking, and talking about the concepts of “diversity”, “culture”, and “cultural responsiveness”. They then moved to considering what was known about effective pedagogy in their particular learning areas and how that related to cultural responsiveness. This was approached differently in each hub, for example:

- in the Māori-medium hub, the inquiries were embedded in kaupapa Māori

- in the Samoan bilingual hub, the focus was on connecting with Samoan students by enhancing their language skills in both Samoan and English

- in the Social Studies hub, cultural responsiveness was addressed as a topic within the learning area, and the teachers were supported to examine the differences between their cultural contexts and those of their students.

The teachers in each hub then discussed what the ideas they had explored might mean for their practice. They reflected upon and clarified their inquiry questions, ensuring that their students’ learning was connected to their own learning. Then each teacher tried a new strategy that they believed to be consistent with a more culturally responsive pedagogy.

If they hadn’t already done so, the teachers set up processes for capturing evidence about the impact of their teaching on their target students, for example, through assessment procedures, interviews with the students, samples of students’ work, video recordings, and observations of themselves and their students.

What does the literature say?

There is an increasing body of evidence about the importance of “culturally responsive pedagogies”. Much of it has come from professional development programmes designed to help teachers shift to practices that take students’ cultural identities into account. Two good starting points are:

- Te Kōtahitanga publications

- literature review on the Experiences of Pasifika Learners in the Classroom.

Culture Counts: Changing Power Relations in Education has been a seminal work for many New Zealand educators. It argues that culture is a critical component of education but that:

"Nevertheless, many educational practitioners continue to ignore culture as a central ingredient in educational interactions. Further, many educators remain ignorant of the fact that they bring to educational interactions their own traditions of meaning-making that are themselves culturally generated. This invisibility of culture perpetuates the domination of the “invisible” majority culture. However, it is not sufficient to simply raise awareness of other cultural backgrounds; it is also important for educators to critically evaluate how one set of cultural traditions (their own) can impinge on another (their “students' ”). Bishop and Glynn, 1999, page 78

The importance of identity and culture to educational success is captured in two Ministry of Education strategies. Ka Hikitia prioritises “Māori succeeding as Māori”. The Pasifika Education Plan calls for all of us in the education system to “step up” for Pasifika education. Each of these strategies then describes what needs to happen in order to improve educational outcomes for these students.

There is also an extensive body of literature about effective pedagogy within specific curriculum areas. For example, teachers who are focused on their students’ literacy achievement can use the Ministry of Education handbooks on Effective Literacy Practice and the Literacy Online website, and teachers of mathematics and social studies can draw on the best evidence synthesis iterations in their learning areas.

Examples from QTR&D

Many of the teachers in QTR&D chose teaching strategies that linked explicitly to their students’ cultures. For example, one teacher explained:

"The study investigates the use of oral language to strengthen comprehension. Samoan people originate from an orators’ society from which power emanates. Knowledge of genealogy and tribal history gave political status, and all such knowledge was passed on orally."

A common theme was the importance of finding ways to build relationships with Māori and Pasifika students that were based on understanding, respecting, and valuing their world views.

"By letting go of the power in my class, I enacted a shift in my pedagogy. I was able to share decision making with the students and class by creating our sharing circle. Students were encouraged to make use of sustained opportunities to participate in creating discussion with their peers and myself. They have taken on a variety of roles in which they share the power with me."

The teacher quoted below sought to make stronger connections between Western science and Māori perceptions of the natural world by building a more reciprocal learning community and by engaging more closely with the students’ whānau and communities.

"The different views of science supported my learning intention for the following study, where I proposed to introduce both views and allow the students to discuss and explore the similarities and differences of those views and thereby construct their own understanding. Involving members of the local community (whānau and elders) with storying related to “Making Sense of the Living World: Ngahere” will not only help to “rekindle traditions” but will also show the students that the teacher is also the learner and so offer a powerful lifelong learning model.

Return to top

The learning inquiry

In this learning inquiry, the teacher investigates the success of the teaching in terms of the prioritised outcomes, using a range of assessment approaches. They do this both while learning activities are in progress and also as longer-term sequences or units of work come to an end. They then analyse and interpret the information to consider what they should do next.

Ministry of Education, 2007b, page 35

The key question for the learning inquiry is: What happened as a result of the teaching, and what are the implications for future teaching?

Two related questions then lead the inquiring teacher back into another round of inquiry: Is there something I need to change? What are the next steps for learning?

The teachers in QTR&D used the information they gathered to reflect critically on the impact of the changes in their practice on their students’ learning. This involved identifying to what extent their teaching had actually changed and the effect of those changes on the outcomes they had prioritised for their target students. Their reflection took place both during and after teaching. It enabled them to identify strategies that had gone well and should be repeated, others that had promise but needed further adjustment, and those that had not worked at all.

Most teachers finished their research by identifying new questions, issues, and concerns to explore and by suggesting possible new outcomes for student learning, so preparing to move into a further cycle of Teaching as Inquiry.

What does the literature say?

Alan Reid stresses the depth of thinking required to reflect critically on the impact of our practice and to use the information to make decisions about where to go and what to do next.

"I understand inquiry to be a process of systematic, rigorous and critical reflection about professional practice, and the contexts in which it occurs, in ways that question taken-for-granted assumptions. Its purpose is to inform decision-making for action. Inquiry can be undertaken individually, but it is most powerful when it is collaborative. It involves educators pursuing their “wonderings” (Hubbard and Power, 1993), seeking answers to questions or puzzles that come from realworld observations and dilemmas" (2004, page 3).

Like Reid, Helen Timperley recommends that teachers inquire and reflect collaboratively in the context of a professional learning community. She stresses, however, that professional learning communities will only lead to improved student outcomes when they are focused on becoming increasingly responsive to their students.

"The effectiveness of collegial interaction needs to be assessed in terms of its focus on the relationship between teaching practice and student outcomes" (2008, page 19).

Examples from QTR&D

Many of the teachers in QTR&D reported on changes in their thinking and practice and in outcomes for their students that were of deep significance in their own learning as professionals.

One teacher discovered a strategy that seemed more effective at scaffolding learning for her students:

"I started this topic with stories about the last few years of the Holocaust and then jumped backwards to answer “How did it get to that?” I think this background knowledge of where the chronology was heading may have given the students a mental construct on which they could hang the new ideas."

Another teacher found that her assumptions about her students’ prior knowledge and her own effectiveness were both challenged:

"When I first started, I had assumed that my passion for art would be infectious to all my students and that we would have 100% student success all around the art department. Was I wrong! Terminology that I had assumed was "common knowledge” was actually unknown to the students."

Many of the teachers felt that the research literature had had a profound effect on their practice:

"Bishop (2001), McNeight (1998), and Wink (2000) suggest that we need to have a classroom environment that engages in reciprocal learning. This means that the teacher is not the fount of all knowledge, but a partner in the learning process. They believe that the teacher needs to listen to the students for their opinions and ideas. Bishop emphasises “student voice” and “power sharing”. So I asked the students what it was that they wanted to learn, and I listened to them."

Teachers commented on the value of inquiry, and many of them noted new questions and issues for future investigation:

This action research cycle sparked a series of questions or strategies that I would like to try. I really began to look at what was working for the teachers down on the marae and decided that I would emulate some of the strategies. I have spoken to our kuia on the marae, and many of the strategies that she uses were reflected in readings about culturally responsive pedagogy (peer teaching, teacher as student). I would really like to find out how closely aligned the E Tipu e Rea whānau is to models of kura kaupapa.

Return to top

References

Aitken, G. and Sinnema, C. (2008). Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Report from the Medium Term Strategy Policy Division. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Anthony, G. and Walshaw, M. (2007). Effective Pedagogy in Mathematics/Pāngarau: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Bishop, R. (2001). Changing Power Relations in Education: Kaupapa Māori Messages for Mainstream Institutions. In The Professional Practice of Teaching, 2nd ed., ed. C. McGee and D. Fraser. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bishop, R. and Glynn, T. (1999). Culture Counts: Changing Power Relations in Education. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Bruce Ferguson, P., Gorinski, R., Wendt Samu, T., and Mara, D. (2008). Literature Review on the Experiences of Pasifika Learners in the Classroom. Wellington: New Zealand Council of Educational Research.

McNeight, C. (1998). Case 2 in Aitken and Sinnema (2008) (see above).

Ministry of Education (2003). Effective Literacy Practice in Years 1 to 4. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2006). Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2007a). Ka Hikitia – Managing for Success: The Māori Education Strategy 2008–2012. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2007b). The New Zealand Curriculum for English-medium Teaching and Learning in Years 1–13. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2007c). Pasifika Education Plan 2008–2012. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education (2008). Te Marautanga o Aotearoa. Folder of materials, including CD-ROM. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2009). National Standards (draft).

Reid, A. (2004). Towards a Culture of Inquiry in Department of Education and Children's Services (DECS) (PDF, 519KB). Occasional Paper Series, no. 1. Adelaide: South Australian Department of Education and Children’s Services.

Robinson, V. and Lai, M. K. (2006). Practitioner Research for Educators: A Guide to Improving Classrooms and Schools. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Corwin.

Te Kete Ipurangi: Aromatawai

Te Kete Ipurangi: Assessment

Timperley, H. (2008). Teacher Professional Learning and Development. International Academy of Education Educational Practices Series, no. 18.

Timperley, H. and Parr, J. (2004). Using Evidence in Teaching Practice: Implications for Professional Learning. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

The University of Waikato: Te Kōtahitanga

Wink, J. (2000). Critical Pedagogy: Notes from the Real World. 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Published on: 26 Aug 2009

Return to top