Ana is deputy principal of a decile 1 secondary school with a high proportion of Māori and Pasifika students. Her inquiry focused on the seventeen students in her year 10 social studies class. Having been born in Sāmoa and educated in New Zealand, Ana said, “My own experience of living in multiple worlds has influenced my approach to teaching and my interest in the experience of Pasifika students.”

Ana’s inquiry question

What impact do language fluency strategies, such as concept circles, have on Pasifika students’ conceptual understanding of systems of government?

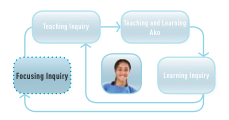

Ana’s focusing inquiry

What was important, given where Ana’s students were at?

Ana’s inquiry was provoked by her concern about three sets of issues:

First, all the students had high literacy needs as revealed by their Paul Nation and asTTle results, and most were speakers of English as a second language (ESOL). This made it difficult for them to express and build upon their conceptual understandings within English-medium settings.

Second, although all the students were Pasifika, some had been born in New Zealand and others were recent migrants. Teasing about people’s grammar, accents, and idioms created tensions that were a barrier to learning.

Third, Ana could see that her students were struggling to make connections between their social learning and the different worlds they experienced at home, church, and with their peers. This did not align with her belief that ... :

... one of the main purposes of social studies teaching in New Zealand is the empowerment of students from diverse backgrounds to participate in society and operate successfully in a democratic system.

Ana hoped that by the end of the intervention, the students would be “able to demonstrate conceptual understandings by speaking confidently and fluently when describing and explaining New Zealand systems of government”.

She called this overarching goal her “focus outcome”.

The focus outcome was chosen to allow me to find out the extent to which language can empower students from non-English-speaking migrant backgrounds.

By giving students the opportunity to 'feel' success, I hoped to both embed the conceptual understandings and give students the improved self-esteem and motivation to acquire more new words.

As her focus group, Ana chose four students who ranged widely in their English language proficiency and confidence and in their engagement in their learning.

She explored their prior knowledge and experiences in relation to three further outcomes:

- their conceptual understandings about systems of government

- their participation in a community of learners

- their thinking about their learning.

Ana planned a range of strategies for monitoring progress towards these outcomes.

Students’ conceptual understandings about systems of government

Ana decided to focus on three sets of data within this outcome.

Vocabulary and key concept

At the beginning and end of the unit, Ana asked the students how many words they knew that are related to the concept of “government”.

Pictures or diagrams showing a system of government

On their first attempt, the students were allowed to access their prior knowledge by selecting examples of such systems within familiar contexts such as their church, family, or sports club.

Concept circles

Ana used these to discover whether the students could explain the relationships between words and concepts about New Zealand’s system of government. A concept circle is an activity in which the teacher writes a concept and associated words or terms in a circle on the board. The students explain the concept, words, and terms and describe the relationships between them in the light of their own experience. They revisit the concept and add new words and terms as they progress through their learning.

Students’ participation in a community of learners, Students thinking about their learning

Ana planned to monitor these outcomes through taking observation notes, interviewing her student focus group, and asking her students to keep “metacognitive diaries” in which they would record their thinking about their learning.

What research evidence did Ana draw on?

Ana read a considerable amount before deciding on the focus for her inquiry. Her decision was influenced, in part, by her reading of Barr (1998). Barr stresses that if students are to participate as citizens in their multiple worlds of family, school, and community, they need to be able to make connections between those worlds.

Ana revisited an article by Hawk et al. titled The Importance of the Teacher/Student Relationship for Māori and Pasifika Students. This article presents evidence from three separate research projects, each of which demonstrated the critical importance of the relationship between the teacher and the learner.

The research clearly demonstrated that when a positive relationship exists, students are more motivated to learn, more actively participate in their learning and the learning is more to form this relationship, the students are less able to open themselves to learning from that teacher. (2002, page 44)

Ana selected her student outcomes after reading an early draft of the social sciences best evidence synthesis (Aitken and Sinnema, 2008). The authors identify five sets of outcomes within the social sciences domain, including participatory and knowledge outcomes. Knowledge outcomes are those “related to students’ understanding of concepts or ideas central to the social sciences domain” (page 37). Subsequently, the Ministry of Education published the series Building Conceptual Understandings in the Social Sciences.

An article by Wendt Samu (2006) was another important influence. Wendt Samu looks at the diversity of the students who come within “the Pasifika umbrella” and the implications of this diversity for teaching and learning.

Anna noted, "It helped me to understand the complexities of the students I was working with. Without understanding the layers, I would have approached the inquiry in a different way. The term “the Pasifika umbrella” includes so many. It made me dig deeper to find the conceptual prior knowledge of my Pasifika students."

Ana’s reading of Corson (1993) and Wink (2000) prompted her focus on language: 'Wink describes language as both a tool and process that enables deep and critical thought and empowers one with the ability to create new knowledge. As 'words develop, thought develops; and as thought gradually develops, the words change with the emerging ideas' (Wink, 2000, p. 36). This notion about the power of language was a significant motivator for me in this collaborative action research."

The link between power and language is also made by Corson, who says that “all kinds of power are directed, mediated or resisted through language” (1993, p. 1) and that for minority cultures “we are bound on grounds of social justice to find ways of accommodating the children of these groups and recognizing their linguistic capital and cultural interests in schools and school systems” (1993, p. 22).

What evidence did Ana use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

Ana’s evidence from exploring her students’ prior knowledge and experiences included the following.

Vocabulary and key concepts

"Results from the group that comprised the target students: three words – government, parliament, Beehive. The students were unable to distinguish between 'government' and 'parliament'."

Picture or diagrams

Student responses showed relationships of top-down control but not how the parts worked together, for example:

- Lupe (explaining a hierarchical diagram): “The pastor is the leader of the church, and the faletua (pastor’s wife) is the leader of the mothers’ group. The youth work together with the choir.”

- Lemaima (explaining a circle drawing with members of the family located around the circle): “My father and my mother talk about some things that happen in our family to me and my sisters.”

None of the students were able to complete a “map” of New Zealand’s system of government. (They had been given pieces of paper labelled with the parts and asked to put them in order.)

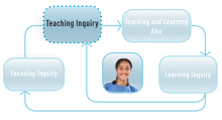

Ana’s teaching inquiry

What strategies were most likely to help Ana’s students learn what they needed to learn?

Ana began her teaching inquiry by reflecting further on the relationship between language, knowledge, and power. It became clear to her that removing language as a barrier to her students’ learning was a matter of social justice.

Ana based her inquiry approach on Pasifika research methodology, which she says is “based on the principles of reciprocity, respect, participation, cultural competency, and meaningful engagement”. She wanted to learn from all the people in the learning community to which she belonged. These included other teachers, the school’s literacy co-ordinator, the students’ parents, the wider community, and the students themselves.

Ana began by inviting the parents of her target students to a shared meal. There she explained the purpose of her inquiry, and the parents expressed their support and shared a considerable amount of additional information about their children. Parents continued to be involved through homework tasks in which they were asked about how their families and church organisations worked and through their attendance at a final presentation.

Ana chose to use language fluency strategies, particularly concept circles. An important aspect of the strategies she tried is that the teacher and selected students model new vocabulary and its use within the strategies.

What research evidence did Ana draw on?

Ana’s understandings about Pasifika research methodology were informed by Gorinski et al. (2006). They discuss this methodology in their report Experiences of Pasifika Learners in the Classroom, which looks at “what ‘works’ for young Pasifika learners in terms of curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment in primary and secondary school education” (page 6). Ana also referred to Anae (2007), who unpacks the Samoan concept of "teu le vā – “tidying up the space" – in relation to establishing relationships between participants in research and inquiry and finding and creating meaning together.

Ana drew on Effective Literacy Strategies in Years 9 to 13 (Ministry of Education, 2004), a professional learning resource that helps secondary teachers select strategies that cater for the literacy and cognitive needs of their students. This resource describes a number of strategies (including concept circles) that teachers can use to expose students to new vocabulary and help them become fluent in using it.

What evidence did Ana use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

In two previous units, Ana had worked hard to use oral language strategies to connect students’ learning to their conceptual understandings. However, despite the students’ willingness to learn, the shifts in their conceptual understandings were minimal.

Ana’s change to language fluency strategies reflected her realisations that she was not providing enough scaffolding for her students and that she had been controlling the learning rather than sharing that control.

Ana's reflections on her practice

- The previous two units of work done by the class showed negligible shifts in their conceptual understanding … all focus learners scored “Not Achieved” in both tests …

- The unit plan was the driver for sequencing the learning activities, rather than the conceptual shifts made by the students; students were “left behind” in the drive to finish a topic …

- The focus of my teaching had been what my students know (or didn’t know); it was my job to ensure that the “empty vessels” were filled with important facts.

Ana decided that she wanted to relinquish some of her control and move to a pedagogy based on she and her students learning together.

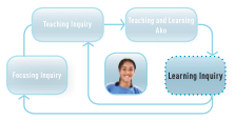

Ana’s learning inquiry

What happened as a result of Ana’s teaching, and what are the implications for her future teaching?

Throughout her inquiry, Ana paid careful attention to the evidence she accumulated about the shifts in her students’ learning, using this information to try to respond more appropriately to the students’ strengths and needs as they emerged. By the end of the intervention, she felt that she had succeeded in making some significant changes to her practice.

These changes had resulted in positive shifts for all but one of her students in their conceptual understandings about systems of government, their identities as learners, and their relationships with one another. The exception was a student whose school attendance was irregular throughout the intervention.

The framework used for explaining what happened

Ana used the four mechanisms outlined in the social sciences best evidence synthesis as a framework for explaining what had happened in her classroom.

Connection

Allowing the students to begin with their own experiences of decision-making processes and systems within their fanau and church provided a foundation for building more abstract knowledge. The use of pictures and diagrams overcame the language barrier and allowed Ana to access her students’ prior knowledge and use it to unpack key concepts.

Alignment

Ana aligned the activities to the intended outcomes and made this clear to the students through the use of learning intentions and success criteria. This meant that the students clearly understood and could monitor their progress towards their learning goals. Repeated engagement in oral activities using an increasing variety of words was reassuring and motivating and enable the students to embed their new vocabulary. Focusing on concepts rather than content resulted in reduced coverage but more opportunities to unearth and address students’ misconceptions. Learning was paced and sequenced in line with where the students were in their learning.

Community

The intervention required the students to speak aloud, often in a strong Pasifika accent. For the students, this was a high-risk activity in which they often made mistakes. It required the development of trusting relationships and mutual respect, reciprocity, and cultural inclusiveness. It required Ana herself to relinquish control of the learning and develop a more reciprocal relationship with her students.

Interest

The creation of a sense of community in which the students had greater control of their learning and felt safe to take risks meant that they became much more focused on their learning. They became immersed in discussion in a way that they hadn’t been before, and they thoroughly enjoyed interacting with each other, engaging in dialogue, and asking questions.

What Ana discovered

An interesting discovery for Ana was the importance of combining pair or group activities with whole-class work in which she could check her students’ understandings, address any misunderstandings, and model the language strategies. Another discovery was the complexity of the connections between different world views.

Western understandings about democracy and individual and group rights are not necessarily the same as Pasifika understandings. Furthermore, as recent migrants, some of Ana’s students and their families had not experienced the systems and processes of government that most New Zealanders regard as routine, such as the electoral cycle. This reflects the importance of cultural responsiveness.

It’s about understanding who they are, where they’re from, and the values they bring to their learning. They are like the gifts our students bring to the learning experience. In terms of being culturally responsive, it’s about respect. I think our mainstream model of education still makes assumptions about people’s world views. It supports a certain world view and not others. Even our understanding and practice of democracy makes a statement about this. In some cultures, democratic decision-making processes accommodate a respect for the role of elders in the community …

It’s interesting how many assumptions we make about what people do or don’t know because of where they were brought up. There are whole different ways of knowing … Concepts like duty, social responsibility, and community have such different meanings for different people.

Future inquiry

Ana was greatly encouraged by the success of her new approach. It seemed to have empowered the students and been a catalyst for compelling shifts in the students’ conceptual understandings. She was left with many questions for future inquiry.

These included:

- What tensions are there for students whose cultural backgrounds present different understandings about significant concepts such as democracy, freedom of choice, equity, and accountability?

- How can teachers align learning experiences to their intended outcomes while meeting their students' diverse motivational needs and interests?

What research evidence did Ana draw on?

Ana used the social sciences best evidence synthesis to make sense of what had happened to her students as a consequence of the changes in her pedagogy. (See Story 6 for a brief introduction to the mechanisms and another example of their use.)

Ana also drew on Guy Claxton (emeritus Professor of the Learning Sciences at the University of Winchester), who describes “split-screen teaching” and connects this concept to the New Zealand Curriculum’s key competencies, as reported in an Education Gazette article (Erb, 2008).

What evidence did Ana use from her own practice or that of her colleagues?

Ana’s evidence in relation to the three outcomes included the following.

Conceptual understandings about systems of government

Taken together, the following pieces of evidence show how the students learned to express a wider range of concepts and describe the relationships between them:

- Vocabulary and key concepts: The three students who had attended most sessions were able to recall between 14 and 23 new words and to accurately define between 12 and 23 of them.

- Pictures or diagrams: All the students were able to draw their own diagrams, correctly identifying the parts of the system of government. They could justify their placement of each part of the system and explain how these parts interacted with at least two other parts.

- Concept circles: In the middle of the inquiry cycle, one student showed that she could describe the relationship between the words she had learned in the concept circle. The student noted:

The relationship between laws and decisions that affect people’s lives is that the parliament can pass laws that affect people, like banning cigarettes, but this can affect people who smoke and the people who make the cigarettes.

Students’ participation in a community of learners, Students thinking about their learning

One student remarked that the Systems of Government unit was the one she had most enjoyed that year “because I learn about the place I live in … New Zealand”.

By the end of the intervention, a student who had previously been too shy to speak voluntarily in the class said, "I learned this [about the Governor General, Cabinet, and Executive Council] by working with Pale. We memorised the meaning of the words and listened to each other talking about the meaning."

Another student, who had previously shown considerable disrespect for those who spoke strongly accented English, wrote, "Our community worked together, helping each other; in other classes, we can only help each other sometimes."

Ana observed that the students were finding it easier to stay on task in discussions. In part, this was a consequence of their greater confidence: "I feel I can talk about the system of government and know what I am saying."

Ana also found evidence that she had relinquished some control of the learning and developed a more reciprocal relationship with her students.

This shift to a more effective learning community is reflected in the following comments from students.

We always share our knowledge with the teacher; and we understand the meaning of the words. But in other subjects, we just find the meaning, and sometimes we don’t understand.

We work better as a learning community in social studies than in other subjects, but we could get better. We still have put-downs.

What happened next?

Ana has kept an eye on this group of students, who are all now in mixed classes. Their motivation to learn has continued, and many have done well, as reflected in their results in asTTle, NCEA internal assessments, and awards handed out at year 11 prize-giving.

Ana’s experience in her inquiry has had an impact on her as both a teacher and a school leader. In her history teaching, she is taking a more collaborative approach and working on making stronger connections to the students’ prior experiences. She is also exploring Guy Claxton’s concept of split-screen teaching, with three screens in mind: content, learning skills, and literacy. She is now adding a fourth screen – the students’ sense of well-being.

As a school leader, Ana is trying to embed the concept of inquiry learning and a community of learners across the school:

"As DP of this school, it seemed very important to me that the inquiry model of teaching is adopted by everyone, but I know how hard that is personally."

"When you think about the journey I took, the impact of the literature, I know it’s a lot to ask. But I think it’s very important."

"In my job, it’s about creating a professional learning community in which learning is the norm. And what I like about it is the connections with The New Zealand Curriculum and its messages about personalising learning and lifelong learning."

Reflective questions

- What questions does this story raise for you and your colleagues about:

- the relationship between language, knowledge, power, and student well-being?

- the different worlds your students inhabit and the connections between those worlds?

- the use of language learning strategies to build students' conceptual understandings?

- the knowledge and understandings students have about key concepts within your learning area and how they may vary for students of diverse cultural groups?

- the kinds of teacher-learner relationships that facilitate learning?

- Pasifika research methodologies and their relationship to the Teaching as Inquiry cycle?

- the tension, given limited time, between breadth of coverage and depth of learning?

References

Aitken, G. and Sinnema, C. (2008). Effective Pedagogy in Social Sciences/Tikanga ā Iwi: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration [BES]. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Anae, M. (2007). Teu le Vā: New Directions in Thinking about 'Doing' Pacific Health Research. Presentation from the Public Health Research Forum 2007.

Barr, H. (1998). The Nature of Social Studies. In New Horizons for New Zealand Social Studies, ed. P. Benson and R. Openshaw. Palmerston North: Massey University ERDC Press.

Claxton, G. (2006). Expanding the Capacity to Learn: A New End for Education? (PDF, 640KB) Keynote address to the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Warwick University, Coventry, 6 September.

Corson, D. (1993). Language, Minority Education and Gender: Linking Social Justice and Power. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Erb, W. (2008). Working out Learning. Education Gazette, vol. 87 no. 22.

Gorinski, R., Ferguson, P., Wendt Samu, T., and Mara, D. (2006). Experiences of Pasifika Learners in the Classroom: An Exploratory Study of Eight Schools. (PDF, 700KB) Wellington: NZCER.

Hawk, K., Cowley, E., Hill, J., and Sutherland, S. (2002). The Importance of the Teacher/Student Relationship for Māori and Pasifika Students (PDF, 172KB). Set: Research Information for Teachers, no. 3, pp. 44–49.

Ministry of Education (2004). Effective Literacy Strategies in Years 9 to 13: A Guide for Teachers. Wellington: Learning Media.

Wendt Samu, T. (2006). The 'Pasifika Umbrella' and Quality Teaching: Understanding and Responding to the Diverse Realities Within. Waikato Journal of Education, vol. 12, pp. 35–49.

Wink, J. (2000). Critical Pedagogy: Notes from the Real World, 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

Published on: 26 Aug 2009

Return to top