Introducing Karori Normal School (KNS)

Karori Normal School (KNS) is a large decile 10 full primary school located in a Wellington suburb next to Victoria University College of Education. The school has a roll of approximately 750 students. Most students are New Zealand European, but students from 39 different nationalities also attend the school. The school serves a community which has high educational expectations for its children, and which is actively involved in the range of opportunities the school organises to share student learning. The school has 34 classroom teachers, and two specialist positions: curriculum leader and teacher-librarian.

The fit between existing school practices and key competencies

Teachers saw the key competencies framework as centred around ideas of lifelong learning and recognised that the framework “aims for the sort of person we want our students to turn into”. In contrast to the Essential Skills, which had been approached as discrete skills in a way that was invisible to students, teachers viewed the key competencies as holistic, and as something they would embed within the curriculum and be explicit about introducing to students.

School leaders at KNS viewed the key competencies framework to be a timely development that could run alongside a review of curriculum and pedagogy and a related programme of whole-school professional development (PD) that started its current focus in 2002. The aims of the review were to create more consistency across year levels in approaches to literacy and numeracy, to examine the balance between curriculum coverage and depth following staff concerns about curriculum overcrowding, and to explore ways to shift pedagogy towards lifelong learning and student-centred approaches. Staff considered that a number of recent and current initiatives and PD opportunities related to this refocusing could potentially provide avenues for exploring and integrating the key competencies into teaching and learning. These are described below.

Developing a framework for integrated learning

To support whole-school consistency, whilst also giving staff scope to target the needs of syndicates and students, KNS had started to base planning around integrated, rather than discrete topics. This approach was viewed as a vehicle to support an increase in student-centred practices at the school as it represented a change from a prior more directive approach to planning discrete topics. Staff considered that past approaches had not empowered them to have ownership over classroom programmes, or tailor them to students’ needs and interests.

At the end of 2005, staff decided on a whole-school umbrella theme for the first three terms of 2006: “Past, Present, Future”. To provide support and guidance for staff to use this new approach to planning, the school had created a specialist curriculum leader position. With a curriculum team, the curriculum leader developed a whole-school curriculum-planning framework. Using the planning framework, each syndicate selected areas to cover within each term theme. To support the integration of the key competencies into teaching and learning, one or two key competencies that were most suited to each theme were incorporated into school-wide plans.

In term 1 Participating and contributing was selected as the focus key competency. In term 2 as part of the “Present” theme, learning activities were structured around the development of scientific knowledge via fair testing. Managing self was selected as the focus key competency. Literacy activities centred on the procedural and explanation reading and writing skills needed to understand and conduct science investigations. The term 2 plan for the years 5/6 syndicate is shown in Diagram 2.

Diagram 2: KNS Term 2 Years 5/6 Syndicate Curriculum Plan

| Term 2 2006 Planning Overview

|

|---|

| Key competency – Managing self Learning intention: The students will: use a rubric to identify their competency.

| Past Present Future Fair testing – Physical and Material World

Achievement Objective: Investigating in Science

Extends experiences and personal explanations of the material and physical world through exploration, inquiry and scientific investigation.

| Learning intention: The students will: be able to work out whether or not a test is fair, and explain why plan and conduct a simple fair test (small groups or independently) use data and observations to construct a reasonable written explanation generate questions that can be answered through scientific inquiry.

|

| Habits of Mind Questioning and problem solving Having a questioning attitude. Developing strategies to produce needed data. Finding problems to solve. How do you know?

| Deep understanding: Scientists develop explanations using observations (evidence) and what they already know (scientific knowledge). A fair test is one method scientists use during their investigations. Fair testing finds relationships between factors (variables). A single variable is changed while keeping other variables the same. Any differences are said to be the result of the changed variable.

|

| Graphic organisers Information webs. Circle maps. Tree diagrams (which can be used to organise information from circle maps).

| Literacy writing Procedural and explanation writing. Literacy reading Reading to: picture books with themes which support the Managing Self key competency. Non-fiction reading to support fair testing focus and the development of scientific knowledge. Reading skills: skim, scan, note-taking and forming questions.

| Representations

Science fair displays:

parents will have an opportunity to visit classrooms with their children and view their work.

| Assessment Student, peer and teacher review of key competency using the Managing Self rubric. Explanation writing – asTTle sample. Teacher observations.

|

| Inquiry focus Introduce aspects from KNS research model as appropriate.

|

|

Lifelong learning

Another school-wide emphasis viewed as related to the key competencies was a focus on lifelong learning. In 2005, staff attended a teacher-only day designed to support the school’s curriculum review process. To develop a shared sense of the student and teacher outcomes they were working towards, they brainstormed the attributes students and teachers would need for the future using the headings: “The Karori Kid” and “The Karori Teacher”. This exercise was also repeated with students. These attributes were then integrated into PD, planning, and formative assessment procedures. A number of other approaches, designed to support students to develop lifelong learning approaches, were also part of classroom practice; for example, a focus on one or two of Costa and Kallick’s Habits of Mind relevant to each unit of work.

Making the process of learning more explicit

The literacy and numeracy PD contracts, in which staff were currently engaged, were also viewed as aligning with the approaches staff intended to use to integrate the key competencies into their programmes. These contracts had a focus on formative assessment, student goal setting, the exploration of a range of strategies, and making the process of learning more explicit to students. To support these approaches, students’ personal goals were taped to their desks in many classrooms.

Connecting the key competencies with other school-wide approaches

School leaders had recently, or were currently, attending PD and visiting other schools to observe practice in a range of areas. This professional learning was shaping school-wide practices at KNS. Areas that were being explored, and which had the potential to inform the school’s approach to the key competencies, included the use of:

- assessment rubrics

- critical thinking strategies, such as De Bono’s Thinking Hats

- co-operative learning strategies

- ICT for learning, such as graphic organisers.

The process: How the school introduced key competencies

School leaders considered it was important that all staff were involved in new initiatives and in exploring changes to practice that might result from these initiatives. To this end, school leaders initially used a whole-school model of introducing the key competencies. As school leaders were also aware that the school had a number of other PD initiatives underway, following a general whole-school introduction to the key competencies, one or two teachers from each syndicate level offered to further develop approaches to integrating the key competencies that could then be shared with the whole staff. The process used to unpack the key competencies with staff is set out in Diagram 3.

Diagram 3: Steps taken by KaNS staff to unpack the key competencies

STEP 1: Whole-school professional development on student and teacher outcomes

In Term 1, school leaders used their understanding of the key competencies, and the descriptions of the key competencies from presentations at the Normal Schools Forum, to introduce the key competencies framework to staff. Staff then examined their existing picture of the attributes of “The Karori Kid” and “The Karori Teacher” and how these fitted with the key competencies.

STEP 2: Continuing whole-school discussion

At subsequent staff meetings, staff were split into vertical groups to share practical ideas about how the key competencies could be integrated into teaching and learning, and discuss key areas such as the connections or overlap between the key competencies and the Habits of Mind.

STEP 3: Syndicate discussions

At syndicate meetings, staff continued their discussions about how the key competencies fitted within the school-wide planning template and their current activities.

STEP 4: Development of a trial rubric for Managing Self

The curriculum team developed a rubric to support teachers to interpret Managing self and to support students to self assess. This rubric was given to each syndicate to use.

STEP 5: Trialling approaches at a syndicate level

In syndicates, staff discussed practical ways to integrate the key competencies into their practice and how they would use the Managing self rubric. One or two teachers from each syndicate offered to develop and trial approaches that would then be shared with their syndicate and the whole school.

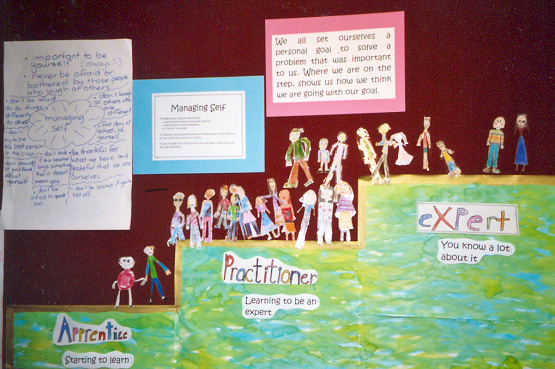

Assessing key competencies

Managing self was the focus key competency for term 2. To support teachers to incorporate this key competency into their programmes, curriculum leaders developed a rubric that covered the four aspects of Managing self they considered to be the most important (exercising initiative, identifying personal goals, taking responsibility for actions, and risk-taking). This rubric included four suggested levels of progression for each aspect, which some staff called novice, apprentice, practitioner, and expert. To develop the rubric staff drew on ideas from recent PD contracts, the rubric developed by Central Normal School, and the rubrics used for assessment in the New Basics programme in Australia. For three of the areas the progressions had been suggested for teachers and students. The fourth area, risk-taking, was left for teachers and students to complete, with support from the curriculum team. Each syndicate was then given the flexibility to interpret this rubric for their own purposes. Teachers adapted the rubric to suit their students. Those in years 1–4 adapted the language, and some teachers decided to use three levels of progression rather than four.

Introducing the key competencies to students

In each syndicate, staff trialled a number of different approaches to integrating the key competencies, some of which are described below. In years 7–8, some teachers started a focus on the key competencies in the first term as students were preparing for camp. Using scenarios related to students’ experiences as a starting point, teachers initiated discussions about Participating and contributing, life skills, managing choices, and risk-taking with students. Some teachers connected the key competencies with other approaches. For example, one used the Thinking Hats as a tool to support students to evaluate which choices were more appropriate. On returning from camp, some teachers asked students to reflect in their workbooks on how they had demonstrated Participating and contributing.

For most teachers, their main focus on the key competencies started in term 2 as they used the school-wide rubric to structure their introduction of Managing self to students. Across syndicates, teachers used similar approaches. Most held discussions with students about what Managing self meant and used brainstorms and class posters to develop a shared language of terms and criteria. Teachers then used these visual aides and the key competency language they had developed to support a range of classroom activities. These activities were all designed to support students to start thinking about Managing self, and reflect on their behaviour, with the ultimate aim of students setting personal goals relating to Managing self.

In years 1–2, one teacher was developing ways to give Managing self more prominence within curriculum activities. One strategy involved focusing on Managing self during group tasks. To set up a cooperative science classification task about zoo animals, the teacher described the steps students would go through. Referring to the criteria about Managing self and Relating to others that the class had developed, the teacher facilitated a whole-class discussion about why it is important to be able to work with people, what good collaborative behaviour looks like, and how to plan and manage your time. During the task students were prompted to reflect on the content of the task, their teamwork, and how they were managing themselves. At the end of the task students were asked to reflect by rating their skills on a 1 to 5 scale against the following statements:

- I followed all the instructions.

- I cooperated with my group.

- I managed my time well.

- I thought about my behaviour.

In years 3–4, teachers were using the Managing self rubric to support student self-reflection about the key competencies. In one class, after an initial introduction to Managing self, in negotiation with teachers, students located themselves on a Managing self continuum that was displayed on the wall. During classroom exercises students were asked to reflect on how they demonstrated the four aspects of Managing self outlined in the rubric. Using this evidence they could then negotiate with the teacher to change their place on the continuum.

In other classes, students and teachers discussed what was going well and not so well in the classroom, and developed strategies to work towards improving classroom interactions. In one class, students set personal Managing self goals. These goals, and strategies to work towards them, were discussed as a class and recorded in students’ workbooks. Students were asked to place themselves on a continuum in relation to their goals. This continuum was returned to periodically as students revised their location. The continuum is shown below in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Managing self continuum

If you cannot view or read this diagram, select this link to open a text version.

Teachers’ reflections on their initial work on the key competencies

Teachers considered that their focus on the key competencies had given them and students a shared language to talk about social skills, behaviour, motivation, and attitudes, and why these were important. They had noticed this language starting to filter through students’ conversations with each other in the classroom and playground. Staff noted that this focus had created space for discussions that recognised diversity and gave students the opportunity to talk about their personal experiences. Both they and students valued these opportunities:

The kids are finding it quite exciting… It’s about them and who they are… They have to think more about themselves in a focused way…

Some teachers considered that this emphasis was assisting them to move from a focus on behaviour management towards assisting students to self-manage and understand the reasons why this might be important. For example, when discussing how students completed their homework teachers asked questions such as “What are the different ways you approached completing your homework?”, “Was that a good choice for you?”, and “What other choices did you have?” Others found the key competencies supported their behaviour management practices. For example they used the Habits of Mind: “impulsivity” and the key competency: Managing self, to discuss behaviour with students.

Teachers commented that the student-centred approaches they used to introduce the key competencies to students linked well with current literacy and numeracy PD on teaching to student needs and making strategies explicit. The key competencies framework supported them to be more explicit about evaluating the process of learning, as this framework encouraged students to think about setting achievable goals in areas other than literacy and numeracy, plan how to achieve these goals, and explore a range of strategies related to these goals.

Some teachers described their initial discomfort about negotiating with students, when their views about students’ capabilities differed from students’ views, and students did not have the strategies to action their goals. Some teachers had left students to self-assess. Others started to develop more confidence in discussing these new goals with students. They had observed that students showed strong support for exploring the key competencies if they were framed as something that could be continuously improved on, and if a climate of positive feedback was maintained. These teachers created this climate by having discussions with students in a matter of fact way and drawing on evidence that they, the student, and their peers had noticed in relation to the class criteria. They reported that students responded well to these discussions, which resulted in teachers feeling more comfortable with this approach:

I didn’t think I would be prepared to deal with things as explicitly as I have…

Other teachers did not have this initial sense of discomfort as discussions of this nature had been an existing aspect of their classroom practice.

Overall, teachers were at different points in relation to integrating the key competencies into their classroom practice. After an initial introduction to the key competencies some had started to embed discussions about the key competencies within curriculum activities. Others noted that the school focus on Managing self had led to it becoming a “subject in itself” rather than being integrated into other activities: “I could throw out the rest of the term because I’m so fascinated!” They suggested that, now a shared understanding about the key competencies had been developed with students, there was a need to start integrating them more into the curriculum.

Making key competencies visible in school life

Presenting and displaying

To make the school’s approaches visible to staff, information about the key aspects of each key competency and the school’s curriculum planning framework was placed on displays in the staffroom. To make the key competencies more visible to students, most classes had key competency posters, brainstorms, or continuums on the wall that students and teachers had developed.

Sharing key competencies with parents

At the stage we visited the school, all parents had not yet been formally introduced to all the key competencies. Parents who attended a recent parent meeting were told about the key competencies and school leaders had also talked to the PTA and board of trustees. Parents were informed in a newsletter about the school’s focus on Managing self, and parents of students in years 7–8 were introduced to this key competency through a homework exercise in which students were asked to detail the different ways they displayed Managing self at home. The school website also includes information about the key competencies and how they are being included in the curriculum.

Reporting

Teachers commented that their focus on the key competencies would give them some standard language to use for reporting to parents. Some were starting to use this language for written reporting. Staff considered that developing strategies for more standardised methods of assessing and reporting would need to be approached with caution.

Connecting with pre-service trainees

Trainee teachers were familiarised with the key competencies by members of the key competency team if they were working with these teachers while they were introducing the key competencies to students. These trainees had opportunities to observe teachers’ work. To ensure that local teacher providers were kept up to date with the school’s work on the key competencies, school leaders had talked to local university staff about the school’s focus.

Student perspectives on the key competencies and school

To gather students’ perceptions on the key competencies, we held a focus group with year 7 and 8 students. The students in the focus group mostly had some form of leadership responsibility such as being part of the student council or a school banker teller.

Learning about and demonstrating the key competencies

Most students in the focus group saw the key competencies to be “skills for life” that they needed to learn at school so that they would be able to function in society:

As you grow up you have to learn to be responsible and understand that actions have consequences. Key competencies get that message across. They come in useful as adults, seeing as you use them in everyday society.

Students perceived the way they learn about the key competencies to be different from other aspects of their learning, in that rather than being told what to do, “we are trying to figure it out for ourselves”. In comparison to other focuses, the approaches taken to the key competencies placed a greater emphasis on their ideas and opinions and allowed for the recognition of individuals’ skills and attributes. Students valued this emphasis and enjoyed the focus on the key competencies. Like their teachers, students thought this approach gave them more responsibility over their learning by giving them the scope to set personalised goals for themselves and to work out strategies to action these goals. Students perceived the key competency focus to provide them with strategies they could use to manage their learning at school, and their homework. At this stage, students noted that most of the focus had been on Managing self.

When asked for situations in which they demonstrated the key competencies, most students talked about how they had demonstrated the three most familiar key competencies ( Relating to others, Managing self, and Participating and contributing) during real-life situations, such as activities on a recent school camp:

[I showed Participating and contributing and Relating to others when I] was at camp and we went rafting. Our rafting group really had to work together and cooperate with each other to ensure we stayed in the boat.

One class was run as a cooperative community. Students noted that this gave them substantial autonomy and enabled them to demonstrate the key competencies as they made decisions, planned, and worked as a team. In general, situations that required teamwork were commonly mentioned as times students demonstrated the key competencies; for example, group discussions concerning school work, being part of a school team for a literacy quiz, or playing team sports:

[I show Relating to others when I] play in my soccer team. Everyone is listening and suggesting things at half-time.

The wider learning environment at KaNS

In general, all of the students considered that they learnt the most when they were doing practical, real, and fun things such as science experiments, technology activities like cooking, and activities on school camp. They also learnt from: discussions with their peers and teachers; feedback from teachers; literacy activities about different styles of writing; and learning different strategies. Some students thought they learnt a lot from cooperative work; others preferred individual work. They appreciated the range of leadership opportunities available to them at the school.

Students’ comments about their learning environment suggest there were substantial differences between the pedagogy used in different classes. Students from some of the classes recognised that the approaches teachers were taking to the key competencies had some commonality with approaches taken to numeracy and literacy, as they were also centred around goal setting and learning strategies. These students felt that they had more autonomy in the classroom and talked about how, during mathematics and other activities, they discussed the strategies they were using with teachers and their peers. They also discussed the reflections they wrote in diaries. Other students commented, “We don’t do much of that.” In their classes, a pressure to complete work meant that reflections were written but not returned to. These students noted that, without discussions and conversations that supported them to develop a next step, the value of these reflections was lost.

Overall, students were very positive about the learning experiences on offer to them, but they also made suggestions about things they did not learn from or which could be improved. Students considered they did not learn by repeating known content or by copying things from books or off the board: “With our class we copy all this stuff off the whiteboard and never use it.” They also found it hard to learn from strict teachers, if they had too many relievers, or if learning was not at their pace: “When things are thrown at you and you don’t have time to digest it.” Students considered their learning and the teaching programme could be improved if:

- they had more opportunity to do sustained work, both in groups and individually, and carry through work to its completion: “We start too many things off…”

- they had more choice over activities so that a broader range of interests were represented

- teachers used different strategies for selecting students to answer questions or for class activities so that students did not feel “picked on” and classes got equal opportunities for school activities and trips.

In summary, students’ comments show that some teachers were using pedagogical approaches that aligned with the theories underpinning the key competencies; that is, approaches that encourage student ownership over learning. Students’ reflections show their support for these approaches. Other staff appeared to be using more traditional approaches. Students identified the need to pare down curriculum coverage in favour of in-depth work. Some staff also identified this need.

Where to next?

The initial exploration of the key competencies had been a fascinating and enjoyable experience for both staff and students at KNS. The way they had approached the key competencies had supported the staff we interviewed to use student-centred practices and make the process of learning more explicit to students. A next step for the school was sharing, with the whole staff, the practices the early adopters had developed. Teachers commented that this could be a challenge given that many perceived their school environment to be pressured by curriculum overcrowding, the amount of other PD initiatives underway in the school, and accountability requirements. Some considered this was likely to impact on their ability to deepen their understanding of the key competencies. They suggested the school was at the initial stages of a journey that needed to be continued:

I’m not sure if our ideas of what they [the key competencies] look like are accurate…I’m not sure as a school if we have developed a clear picture yet.

Exploring more formal assessment of the key competencies was another next step. Staff had decided to approach this task slowly. The need to rationalise the school planning template by exploring the overlap between the key competencies and existing tools and strategies such as the Habits of Mind, Thinking Hats, and cooperative learning strategies, was also suggested by some as a possible next step.

Published on: 20 Sep 2007

Return to top