Unpacking the reading and writing standards (archived)

The theoretical basis | Reading | Writing

The standards for reading and writing establish the level of literacy expertise that can reasonably be expected of most students by the end of each period or year of schooling, from the first year of school through to the end of year 8 (However, students start at different points and progress at different rates. That is why, when interpreting achievement, it is important to consider both the student’s rate of progress and the expected standard).

The framework of the standards is the same as that of the Literacy Learning Progressions. This framework describes the early years in terms of the time students have spent at school (that is, after one, two, and three years at school) and the later years in terms of their year level (for example, by the end of year 4). (Because students in New Zealand generally start school on their fifth birthday, the first three standards need to be used after one, two, and three years at school.) This is because students’ year level, by year 4, becomes more significant than the time they have spent at school. In years 4–8, students develop their expertise in selecting and applying their literacy knowledge and skills in order to engage effectively with increasingly complex texts, tasks, and curriculum content (that is, subject matter).

The standards focus on the purposes of reading and writing for each year of schooling, deliberately using the phrase 'in order to meet the reading [or writing] demands of The New Zealand Curriculum' to emphasise the importance of reading and writing in all areas (In the first writing standard and the first three reading standards, the wording differs but the emphasis on supporting learning in The New Zealand Curriculum is unchanged).

There are skills, knowledge, and attitudes that students must develop in order to read and write the texts that will enable them to engage with all learning areas of the curriculum. While some of these texts will be literary texts (in which case they will almost always be taught within the English curriculum), many of them will be non-fiction texts, such as information reports and procedural texts, which provide key content for particular areas of the curriculum. The forms that these texts take, the vocabulary they include, and the features that they present are often quite specific to particular subjects.

The reading and writing standards are intended to help teachers become more aware of the consequences that their choices of written texts and related tasks have, for their students, in particular curriculum areas.

The theoretical basis

The theoretical basis for how literacy develops is described in the Ministry of Education handbooks Effective Literacy Practice in Years 1 to 4 and Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8. These theoretical understandings underpinned the development of the Literacy Learning Progressions and also, where appropriate, the development of the English Language Learning Progressions.

In broad terms, the acts of reading and writing have three main aspects, which readers and writers use in integrated ways (Luke and Freebody, 1999). The three aspects are:

- learning the code of written language

- making meaning

- thinking critically.

In the reading standards, these three aspects are specifically included because a student needs to demonstrate all three in order to be considered a successful reader. Each standard states:

- 'students will read, respond to, and think critically about … texts'.

Reading involves learning the code, making meaning, and thinking critically, and students demonstrate that they are using the three aspects in integrated ways as they respond to the texts they read. See The layout of the reading and writing standards for further explanation of the terms “read”, “respond to”, and “think critically about”.

In the writing standards, the term “create” is used to cover all three aspects as well as the different processes that students use when they write for specific purposes. Each standard states:

- 'students will create texts … to meet specific learning purposes across the curriculum'.

Developing expertise

Learning to read and write is a complex, cumulative process. Students build on their existing expertise and use their developing knowledge and skills in different ways. Despite these differences, students need certain knowledge and skills in order to be able to develop their independence, fluency, and range. These have been described as 'constrained skills'. They include, for example, learning to read from left to right and developing awareness of letter–sound relationships.

… some reading skills … are constrained to small sets of knowledge that are mastered in relatively brief periods of development. In contrast, other skills such as vocabulary (learning), are unconstrained by the knowledge to be acquired or the duration of learning.

Paris, 2005, page 185

'Unconstrained' knowledge and skills, such as those used for comprehension, are more dynamic and continue to develop over a lifetime.

As students master the 'constrained' skills involved in decoding, their reading becomes more fluent, which frees them to use more of their cognitive resources for the complex 'unconstrained' task of working out text meaning. Similarly, as students master the 'constrained' expertise needed to record sounds, spell words, and form sentences, they become more fluent writers and can then apply more of their thinking to conveying meaning in increasingly

sophisticated 'unconstrained' ways.

Ministry of Education, 2007, page 4

In reading, the same text may be a starting point for many different curriculum tasks. In writing, on the other hand, a text is often created to meet specific demands in a particular curriculum area. The standards describe reading and writing separately, but they are increasingly used together, for example, when students need to locate and record information.

The National Standards address reading and writing equally. However, the following section has a particular focus on reading in years 1–3 because the reading standards for these years are based on the levels of the Ready to Read series. Teachers need to understand what the Ready to Read levels mean in terms of the challenges in the texts and how these are designed to support the development of particular reading behaviours.

Reading

Reading in years 1-3

The foundations of reading and writing are built up during the early years at school. Many of the texts and tasks used in these years focus more on literacy than on developing skills and knowledge across the wider curriculum. For years 1–3, the reading standards refer to the colour wheel levels used for the Ready to Read series. These reading levels are described in more detail below. (A generic description of the characteristics of texts at Green, Turquoise, or Gold accompanies each of the first three reading standards. The specific features of texts at each level are described in more detail as part of the illustrations for the standards.)

The Ready to Read series

The Ready to Read series is the core instructional reading series for New Zealand students in years 1–3.

The texts are levelled according to the suggested guided reading level for each one, and a colour wheel (with a “G” for guided reading beside the appropriate colour) is printed on the back of each book. The colour wheel starts with Magenta (also known as the emergent reading level) at “12 o’clock” and moves clockwise through the early reading levels (Red, Yellow, Blue, Green) and fluency levels (Orange, Turquoise, Purple, and Gold). There are sub-levels within each colour wheel level (for example, Green 1, Green 2, and Green 3).

Ready to Read texts for students in the first year of school are relatively short and use mostly familiar vocabulary and simple sentence structures. As the students read these texts, teachers support them in drawing on their oral language, and on understandings gained from their own writing, to acquire and consolidate basic reading skills, letter–sound knowledge, and automatic recognition of an increasing range of high frequency words. The students gain control over a range of reading processing and comprehension strategies. These are described in more detail in the Literacy Learning Progressions.

For students in their second and third years at school, the level of text difficulty increases gradually in such aspects as vocabulary, text length, complexity of text structure, students’ familiarity with the content, and how explicitly the content is stated. Each student brings a unique combination of prior knowledge to their reading, so there is always variation in how easy or difficult individual texts are for particular readers.

As students progress through the levels, they build a self improving reading process, in which they practise, refine, and adapt their reading strategies and their critical thinking. The texts become longer and more complex, so students are required to deal with bigger chunks of information as they process text. The texts also have an increasing proportion of unfamiliar vocabulary and language structures, and they include a wider range of text structures, which supports cross curricular reading and writing. As they progress, students also read text for meaning in more and more complex ways. Increasingly, as they progress through the levels, the texts that students read are likely to inform their writing.

Students are likely to be introduced to each Ready to Read or Junior Journal text within a shared or guided reading lesson, where teachers help readers to draw on and develop their own problem-solving strategies to read, respond to, and think critically about the text. After the initial reading, students may reread these texts many times. They could reread them, for example, within the same lesson, in the context of a particular task, or as part of their independent reading at home or at school.

The Ready to Read Teacher Support Material (Ministry of Education, 2001–) provides extensive information about literacy teaching in years 1–3, along with notes for each title, which are available both in hard copy and online. The publication Sound Sense: Phonics and Phonological Awareness (Ministry of Education, 2003) has also been distributed to all New Zealand schools with year 1–3 students.

Reading at Green level

Students who can read texts at Green level have learned to draw on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes described in the Literacy Learning Progressions to build their knowledge about language, texts, and reading and to develop a personal repertoire of reading processing and comprehension strategies.

Students at this level usually read silently but may quietly verbalise at points of difficulty. They use a range of sources of information in text, along with their prior knowledge, to make sense of the texts they read. They do this by looking for and drawing on such features in the text as familiar and meaningful content, high-frequency vocabulary, known letter clusters and spelling patterns, punctuation, contextual clues for unknown topic or interest vocabulary, and the illustrations. The print is becoming their primary source of information. With some teacher guidance, these students can relate their prior knowledge to information in the text, make simple inferences, and think more deeply about the ideas in the text.

Texts at Green level have up to about 300 words and can be read comfortably in one reading session. They have one storyline or topic, and the contexts and settings are generally familiar to students through their prior knowledge and experiences (or the teacher may discuss them to make them more accessible). Features that are new or more common at this level include diagrams and speech bubbles, which require the reader to 'pull in' the information and add it to their existing understanding of the running text. By the time they are reading at Green level, students will be using punctuation such as full stops, commas, exclamation marks, question marks, and speech marks to help them construct meaning and to enable them to read orally with smooth, fluent phrasing.

Students are becoming increasingly independent in monitoring their own reading and finding ways to solve the problem when what they are reading doesn’t look right, sound right, or make sense to them. They are beginning to develop metacognition.

Students meeting the standard at this level can read seen texts at Green with at least 90 percent accuracy.

Reading at Turquoise level

Students continue to draw on the knowledge, skills, and attitudes described in the Literacy Learning Progressions to build their knowledge about language, texts, and reading and to develop a personal repertoire of reading processing and comprehension strategies.

Students are reading with increasing independence and fluency. They can read aloud for specific purposes, with appropriate intonation, expression, and phrasing. They use multiple sources of information in text, along with their prior knowledge (which includes ideas and information from their culture, from their language, and from other texts they have read), to make meaning and consider new ideas. They draw on their increasing knowledge of spelling patterns and language structures to solve new challenges, including multi-syllabic words.

Texts at this level have approximately 300–500 words. The settings and contexts may be outside students’ direct experience, but they can easily be related to their prior knowledge. For example, students who read Inside The Maize Maze (Holt, 2004) may not have been inside a maze, but they will have had the opportunity to read The Gardener’s Maze (Meharry, 2002) at Green level.

Some features that are new or more common at this level include labelled diagrams, inset photographs, and bold text for topic words. All of these require the reader to 'pull in' the information and add it to their existing understanding of the running text. There is more frequent use of both dialogue and complex sentences, and so students need to notice and use punctuation as a guide to phrasing and meaning.

Compared with texts at Green level, Turquoise texts have a greater proportion of implicit information and of illustrations that may suggest new ideas or viewpoints. With teacher guidance, students draw on a wider range of comprehension strategies to make sense of what they read and to think more deeply about it. For example, they may need to summarise the main points or events in a text in order to keep track of them, or they may use a simile in the text to help them visualise an event or idea.

Students continue to develop their metacognitive awareness. Their increasing independence shows itself as they monitor their own reading and problem-solve when they lose meaning, both at the sentence level and across larger sections of text.

Students meeting the standard at this level can read seen texts at Turquoise with at least 90 percent accuracy.

Reading at Gold level

Students confidently use a range of processing and comprehension strategies to make meaning from and think critically about longer and more complex texts. They monitor their reading, drawing on a variety of strategies (at the sentence, paragraph, and whole-text level) when their comprehension breaks down.

Texts at Gold level may have more than 500 words and may be read over more than one reading session. Some of the settings and contexts are outside most of the students’ direct experience and involve shifts in time and place. This requires students to make connections to aspects of the text that are familiar to help them build a bridge to the new information. For example, in the text Sun Bears Are Special (Werry, 2002), students may not know about sun bears, but they can draw on what they know about bears, wild animals, and/or zoos.

Compared with texts at Turquoise level, texts at Gold level are longer and more complex. They are commonly organised into paragraphs, and the information and ideas are stated less explicitly and have less support from illustrations. This means that students need to identify and keep track of ideas and information across longer sections of text and look for connections between ideas and information. In non-fiction texts, students use such features as subheadings, diagrams, maps, text boxes, footnotes, glossaries, and indexes, along with the running text, to help them identify key points and understand new ideas. Students continue to draw on their developing spelling and language knowledge to decode and make sense of new vocabulary and of language used in unfamiliar ways.

With teacher guidance, students are beginning to use texts more often to meet demands across the curriculum. They are also preparing for the transition to the School Journal as their main source of instructional reading material.

Students meeting the standard at this level can read seen texts at Gold with at least 90 percent accuracy.

Reading to meet the demands of curriculum tasks in years 4-8

As at earlier levels, each reading standard is accompanied by a description of the key characteristics of the texts students will read as they work at or towards the relevant levels of the New Zealand Curriculum. The standards are illustrated by texts appropriate to each level, which are annotated to make explicit the ways in which text complexity increases at each level. The illustrations also show how students use texts in increasingly complex ways as they progress.

The first part of the standard describes the overall reading competence ('read, respond to, and think critically about') expected at a specific curriculum level. For example, by the end of year 4, the texts will be those that students need to read 'to meet the reading demands of the New Zealand Curriculum at level 2'. A student nearing the end of year 4 could be expected to read appropriate texts selected to support learning in any area of the curriculum at that level.

The second part of the standard describes the key purposes for students’ reading ('locate and evaluate … generate and answer questions') as they carry out curriculum-related tasks. At each year level, these purposes increase in complexity and scope.

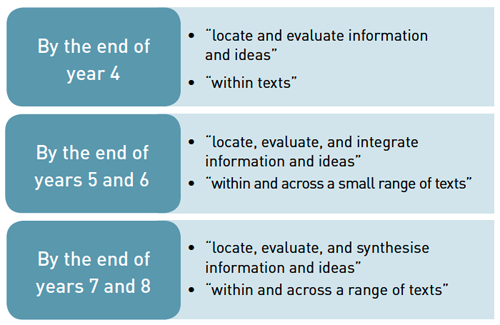

The diagram below shows how two key phrases used in the reading standards change from level to level, clarifying students’ expected progress.

If you cannot view or read this diagram, select this link to open a text version >>

As students move through school, they are expected to process ideas and information across an increasing number of texts and parts of texts. For example, a year 4 student will find several pieces of information from different places within one text, but by year 8, that student will draw on several different sources of information. This could be within the context of a research project: for example, a student inquiring into the causes of pollution in a local stream might refer to scientific and anecdotal reports, newspaper articles, letters to the editor, websites, and other sources of information, some local and others more remote.

Tasks, like texts, become more complex as students consider ideas and information in different ways. There is a 'gear shift' from locating and evaluating items of information on a topic through to locating, evaluating, and synthesising information from several different sources.

Although the text and task demands of the curriculum may appear similar in years 5 and 6, and in years 7 and 8, the sophistication with which students are able to carry out such tasks increases from one year to the next. As students read and write to communicate increasingly complex information and ideas, the uses that they make of the ideas and information also increase in complexity.

Students moving up through the levels of the New Zealand Curriculum need to develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that will enable them to engage with increasingly complex tasks and texts. The Literacy Learning Progressions underpin the reading and writing standards, describing in detail the behaviours that reflect the appropriate knowledge, skills, and attitudes at each year level.

Key characteristics of texts at each level

For each standard, some key characteristics of texts at that level are described. These descriptions will help teachers to develop their expertise in selecting texts that are appropriate for their students. They show how the texts at each successive level become more complex in terms of content and theme, structure and coherence, and language. The descriptions have been carefully developed to guide teachers’ decisions as they select appropriate texts, not just for reading instruction but for all curriculum tasks.

The illustrations that accompany the standards for after one, two, and three years at school show the colour wheel sub-level of each text. The illustrations that accompany the standards for the end of years 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 show the noun frequency level of the text. The Noun Frequency Method (Elley and Croft, 1989) is widely used as a measure of text difficulty. However, this measure does not always reflect text features or the complexity of themes, concepts, or structure.

The relationship between the text, the complexity of the task, and the student’s existing knowledge and expertise determines the challenge (difficulty) of the text for the student. When making decisions about text difficulty, teachers should use their judgment, which will be based on their knowledge of the text, of their students, and of the 'distance' between the text and each student’s experiences.

Sources of appropriate texts to read

For the reading standards, there are suggested sources of texts appropriate for readers at that level (which can also be used as models for students’ writing). In the early years, these are texts from the Ready to Read series. (At these levels, texts for learning across the curriculum are usually texts that the teacher reads to the students.)

The reading matrix in The English Language Learning Progressions (ELLP) gives a broad overview of the features of texts that are suitable for students at each of five stages of English language acquisition. ELLP also provides examples of such texts for each of three bands of year levels. (See page 31 of the ELLP introduction booklet.)

Return to top

Writing

Writing to meet the demands of curriculum tasks in years 1-8

The aim of writing instruction is to build students’ accuracy, their fluency, and their ability to create meaningful text. For information about the instructional strategies and teaching approaches that teachers can use to help students achieve this aim and meet the early writing standards, refer to chapter 4 of the Effective Literacy Practice handbooks.

The first sentence of each writing standard for all year groups (except students after one year at school) states that students 'will create texts in order to meet the writing demands of the New Zealand Curriculum' at specified levels.

The second sentence describes the ways in which students use writing ('to think about, record, and communicate experiences, ideas, and information') and the purposes for writing ('to meet specific learning purposes across the curriculum'). This sentence of the standard is expressed identically for each year, but the accompanying material describes how writing is used with increasing sophistication and complexity as students move through the levels of the curriculum and work with more challenging content. The key phrases in this sentence apply at all levels of learning.

Key characteristics of students' writing at each level

Each standard is accompanied by a description of the key characteristics of students' writing that can be expected at that level. These descriptions highlight the increasing demands in terms of the processes that students use as they write for specific learning purposes across the curriculum as well as in terms of the increasing complexity of the texts they create.

The standards are illustrated by examples, appropriate to each level, of unassisted student writing in a variety of curriculum areas. These illustrations are accompanied by annotations, which make the development of the writing explicit. (Refer to the glossary for an explanation of what is meant by 'unassisted student writing'.)

Published on: 19 Oct 2009

Return to top