Teachers are responsible for planning, developing, and reviewing the classroom curriculum. Making curriculum accessible for all students may require "thinking outside the square" in daily practice. This requires you to be prepared to do things differently, to work towards a shift from being a "routine expert" to an "adaptive expert" (Timperley, 2011). You will best achieve this when working as part of a collaborative, supportive learning community.

Effective planning includes thinking flexibly about how to organise teaching and learning. For example, a class may all be working in the same learning area and participating in shared learning activities. At the same time, some students may be working with different content, within different curriculum levels, toward different learning outcomes, or in relation to different assessment criteria. The students and their whānau should contribute to decisions on these different approaches in the light of the outcomes that are of value to them.

The general principle within such flexible approaches is to be as unobtrusive as possible while still ensuring that students’ individual learning needs are met. When providing access to the curriculum, you and the teams working with students who need additional support should first consider whether the students can pursue the same learning outcomes as their classmates. Secondly, you should consider whether a learning programme is needed that has broadly similar learning outcomes for the whole class but appropriately meets the learning needs of these students at their levels. Thirdly, some students will need individualised content and individualised supports.

In Example 8, a teacher uses mixed ability groups, differentiated content, adaptations such as visual representations, and support from a teacher’s aide to ensure all his year 9 students can engage in shared mathematics tasks.

Two key approaches for effective planning and teaching are differentiating and adapting (Mitchell et al., 2010). Most teachers already use both these approaches to some extent. As you develop your expertise with these approaches, you will:

- recognise that units of work can easily be modified in the classroom programme to cater effectively for students with diverse needs, by using a range of approaches and strategies in planning and teaching

- recognise that some students need multiple opportunities to engage with a range of materials to support their understanding, and that these opportunities may involve using assistive technology or simple adaptations

- reflect on and evaluate multiple ways students can demonstrate their understanding in different learning areas; for students with diverse needs, it may be at the same level or a different level to their peers

- identify ways that all students might assess their capabilities and reflect on their own learning.

Differentiating the classroom programme, adapting the supports

Giangreco, Cloninger, and Iverson (2011) developed a framework to broadly characterise each student’s participation in learning along two dimensions:

- the programme – what is taught (the classroom curriculum), annual goals, specific learning outcomes, and so on

- the supports – what is provided to assist the student to access and achieve educational outcomes, including materials, people (such as specialist teachers), specific teaching strategies, changes in the classroom and environment, and so on.

The school and classroom curriculum can be made accessible to all students through:

- differentiations: changes to the classroom programme – the content of the school and class curriculum and expected responses to it (the "what")

- adaptations: changes to the supports – the school environment, the classroom, teaching strategies, and teaching and learning materials (the "how").

Where some parts of the curriculum content need to be individualised for some students, you can differentiate your classroom programme using two approaches that Giangreco (2007) discusses: multilevel curriculum and curriculum overlapping1. Both approaches support students1 who require additional support to fully participate in classroom learning.

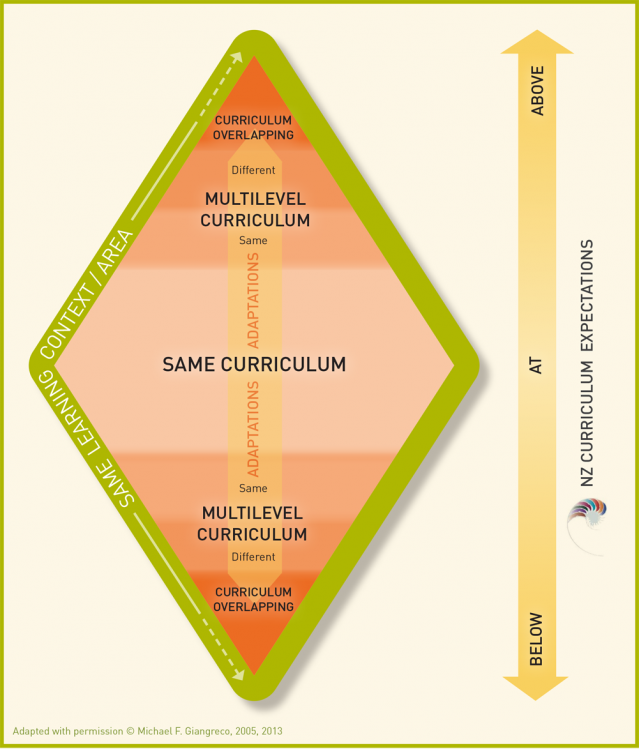

Figure 5 illustrates these different types of differentiation within the classroom curriculum.

Figure 5: Differentiation within the classroom curriculum

If you cannot view or read this diagram, select this link to open a text version.

The different approaches shown in Figure 5 are discussed below. In all the approaches, students work within the same learning context (that is, in the same physical location and related learning experiences). They also work in the same learning area (or areas, for an integrated unit or activity), although this is not always the case for curriculum overlapping.

In same curriculum, students experience the same content and activities, the same level of complexity (curriculum level), and the same number of learning outcomes to be achieved. For example:

A class is mostly working at level 3 in science and are learning about the concept of a fair test. Groups of students are required to set up four pots that have the same amount of soil and the same seed, and that receive the same amount of water each day. One pot is given some fertiliser to see if this makes a difference. The learning outcomes are understanding the importance of controlling variables to determine what makes a difference, and understanding how an adequate sample size makes a test more robust and minimises other factors.

In 'multilevel-same curriculum', students experience the same content and activities as the rest of the class, but the level of complexity and number of learning outcomes are adjusted in keeping with the students’ learning strengths and needs. For example:

In the science unit, Joel and Tama set up the same experiment using the four pots and are expected to understand that one plant grows more quickly because it receives some fertiliser. They are not expected to work on the other learning outcome related to sample size.

In 'multilevel-different curriculum', students experience different but related content and activities, and the level of complexity and number of learning outcomes are adjusted in keeping with the students’ learning strengths and needs. For example:

In the science unit, Sharon is learning how to pot up a plant, and she uses an activity that involves matching pictures of plants with seeds to identify what the seed she is planting will turn into.

In curriculum overlapping, students may participate in similar activities to the rest of the class, but the level of complexity and number of learning outcomes are significantly adjusted in keeping with the students’ learning strengths and needs. The learning outcomes cover more than one area of the curriculum – generally the area the rest of the class is working in, as well as, for example, social sciences, health and physical education, English, or the key competencies. For example:

In the science unit, Katie helps her group set up the experiment. However, the targeted learning outcomes for her relate to communication (from the learning area of English) and the key competency of participating and contributing. With adult support, she uses a visual schedule to follow the instructions and sequence of activities and works on maintaining attention and turn-taking.

Airini excels in scientific investigations and is an advanced reader, absorbing several library books a week. She enjoys working in the school’s vegetable garden, which she helped design in the gifted programme and now maintains as a member of the student council. While other students are working on the fair test experiment, Airini is reading cultural folklore about plants. She loves the Chinese story The Empty Pot, and, based on it, she and her teacher agree she should design an experiment around her question, "What happens when seeds are heated to different temperatures before planting?" Airini develops hypotheses and procedures for data collection. She will share her research results with the student council at their planning meeting for the spring garden.

As Figure 5 demonstrates, multilevel curriculum and curriculum overlapping are appropriate for students working both above or below most of their peers2. Students with gifts and talents (such as Airini), including those who are twice exceptional (such as Kathryn below), also benefit from them:

"Although multilevel curriculum and curriculum overlapping are primarily ways to include students with disabilities, they also enable more meaningful participation for students functioning above grade level. Applying multilevel curriculum allows teachers to stretch their curriculum away from a ‘middle zone’ in which all students share the same curricular content, level, and amount of work."

Giangreco, 2007, page 5

In Example 6, all the students in a years 4–5 mathematics lesson are learning about fractions. Most students are solving word problems at curriculum level 3. The teacher supports some students to solve different word problems at level 2, and one student explores fractions using objects and pictures.

In Example 4, an English teacher differentiates a year-13 oral presentation unit for students working at NCEA levels 1 and 2, and, in collaboration with the Learning Support Coordinator, uses curriculum overlapping to include a student who is working towards a curriculum level 1 goal in the arts.

Kathryn is a year 6 student who has been identified as ‘twice exceptional’. She is articulate, has an extensive vocabulary, and can confidently discuss and debate complex issues in a clear and logical way. However she has significant difficulty capturing her thoughts and opinions in written form. Consequently, although she has been assessed as having above average intelligence, her literacy and numeracy skills are well below national expectations for her year level. Kathryn receives support from an RTLB, who has been investigating using digital technologies to enable her to better demonstrate her learning. Her teacher has been providing her with more time to complete written tasks in class, and he has been exploring her passions and interests in order to motivate her to further develop her literacy and numeracy skills.

If differentiating the programme is about the "what" of teaching, deciding on adaptations is about the "how". Once you have identified specific content you intend to teach within their classroom curriculum, you need to decide how you will ensure that all students will be able to access this content. This may involve making changes to the learning environment, adopting specific teaching strategies, modifying teaching and learning materials, or adjusting a task or activity.

Some examples of how you can adapt supports are:

- using cooperative learning groups

- using visual representations – such as graphic organisers, visual timetables, and Venn diagrams – to organise information and reduce the amount of text required

- providing written or visual versions of spoken material (for example, sign language, transcripts for videos)

- providing adapted computer keyboards or other alternatives to the standard keyboard and mouse (for example, switch access with corresponding software)

- using tactile equivalents of written or visual material (for example, Braille, three-dimensional objects)

- using interactive web tools and social media (for example, interactive animations, chats)

- arranging the class layout so that specific students are close enough to clearly see the whiteboard or hear instructions

- reducing noise for students who find it distracting (for example, by providing ear muffs or sound-proofed quiet areas in the classroom).

In Example 2, the teaching team in a years 4–5 class uses a range of classroom and task adaptations that allow students with additional learning needs to generate and express ideas in a poetry lesson.

In Example 9, a years 5–6 teacher adjusts the tasks and learning materials in a science activity to ensure all students remain engaged and learn.

Return to top

When are adaptations and differentiations needed?

The goal for teachers is to provide meaningful participation for all students within the classroom curriculum. To achieve this, you need to make decisions around curriculum content and level, environment, teaching and learning materials, and responses expected for and by students.

A general guide when deciding on adaptations and differentiations is to change as little as possible while still ensuring that students’ individual learning needs are met. Some students may need only adaptations to access the curriculum – for example:

Daniel has a hearing loss. Mr Jones is trialling a Soundfield system, which could help Daniel. This will only be effective for him when he wears his hearing aids. Mr Jones has asked the specialist teacher (RTD) to support Daniel to understand the benefits of wearing his hearing aids. This system may also help other students in the class who find it difficult to concentrate or who have auditory processing difficulty.

Alannah has severe dyspraxia so struggles to reach the same writing output as others in the class. However, she can achieve the same outcome as everyone else when she uses her iPad. A teacher’s aide with good knowledge of assistive technology makes sure that her iPad can access the class technology systems.

Richard’s teacher gives instructions once for all the class, then repeats them using shorter sentences and less complex language for Richard, who has difficulty processing language.

Other students may need only differentiations to access the curriculum – for example:

The class is conducting an inquiry into their local environment. Students can each select new spelling words from a vocabulary list the class has brainstormed for the inquiry. Dennis knows that he can comfortably learn five new words in a week, and that he will need to consolidate them by putting each of them into a sentence.

A few students will need both adaptation and differentiation but rarely on a full-time basis – for example:

Julie’s teacher is aware that Julie trips over things easily, so she has arranged the classroom furniture to provide a clear and easy passage. She knows that Julie struggles to find her bag to get her play lunch because she is smaller than other members of the class, so her bag is on a low hook and a friend helps her to find it. Julie is learning to recognise and write her name – although others in the class are writing a sentence. She needs to use a pencil grip to manage the pencil. The teacher supports Julie during writing to guide where to start each letter.

Grace has autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and is working within level 1 of the curriculum in her year 5–6 class. She has an Individual Education Plan (IEP) which shows the goals her team have agreed on and the aspects of learning that require adaptations or differentiation. Her teacher and classmates use non-verbal visual supports for both social and academic prompts. Her current focus is a social learning goal to take turns.

It is important to acknowledge that individual students may require access to some or all options throughout a school day or even in one lesson or task. The options should be viewed as being fluid rather than static. Remember the principle of using the least intrusive option available that meets the student’s needs. For this reason, Giangreco (2007, page 5) cautions against too readily adopting curriculum overlapping:

"In the interest of access to the general education curriculum teachers and teams working with students with disabilities should first consider whether the student can pursue the same learning outcomes as classmates or whether multilevel curriculum and instruction will provide enough accommodation before using curriculum overlapping."

As a group, discuss how differentiation and adaptation are currently evident in your planning and teaching.

• Can you think of a specific example that illustrates each approach?

• How could you use Figure 5 in your planning processes to include all students?

Return to top

Shifting teachers’ practice

Shifting teacher beliefs and actions is an important focus for inclusive practice because teacher beliefs and attitudes can support or limit a student’s access to learning. As teachers build towards inclusive practice their beliefs and attitudes become more inclusive and they move away from practices that limit learning opportunities for everyone.

The following table lists some of the ways in which teachers shift their practice as they plan to meet the needs of all their students. (The last three rows are specific to secondary teachers.)

Working within a group of teachers, discuss how your beliefs and attitudes are reflected in the table.

| Moving from

| Moving to

|

|---|

| Beliefs and attitudes that limit opportunities to learn

| Beliefs and attitudes that support opportunities to learn

|

| Low expectations of student learning, progress, and achievement

| High expectations of student learning, progress, and achievement

|

| A one-size-fits-all curriculum

| Curriculum access that may differ for different students, but curriculum for all

|

| Teachers not knowing how to teach some students

| All teachers being capable of teaching all students, with support when required

|

| A belief that “It’s not a classroom teacher’s job to teach ‘these’ students.”

| A belief that the learning of all students is the responsibility of all teachers

|

| An attitude that any student with special education needs will require a teacher’s aide

| Support in the classroom that is coordinated and appropriate

|

| The teacher’s aide working with the student

| The teacher’s aide supporting the teacher to include all students

|

| A belief that “These students do not belong in a mainstream class, they belong in the unit.”

| A belief that all students belong in the classroom, learning within the NZ Curriculum

|

| Teachers feeling isolated

| Coordinated support for teachers and students

|

| Someone else planning for students with special education needs

| Collaborative planning with the LSC/SENCO, student, and whānau

|

| Teachers teaching their subject

| Teachers teaching all students

|

| An examinations-only focus

| All students having the opportunity to undertake appropriate assessment

|

| Restricted options and pathways post school

| Meaningful pathways supporting citizenship, full participation, and lifelong learning

|

[1] In New Zealand, teachers are familiar with the concept and approach of differentiated instruction, usually to meet learning objectives within the same curriculum level for all students in the class. Multilevel curriculum and curriculum overlapping, on the other hand, aim to meet learning objectives within several curriculum levels for students in the class.

[2] And of course, for an individual student "same curriculum" may be appropriate for one learning area (for example, mathematics) and multilevel curriculum or curriculum overlapping for another (for example, English).

Return to top